Several years ago, I went in search of an audience for my students, although at the time I didn’t know that was what I was up to. I’d seen enough student writing to know I wasn’t doing something right in my instruction. My students were smart, interesting and capable of all manner of argument, but their writing didn’t reflect that. However, they were willing to risk suspension by breaking through the district’s internet firewall to reach sites like Myspace and Facebook where they wrote (Wrote!) about things they cared about in ways that reflected their personalities. This was what I was looking for. So I started a website where my students and I could build on the conversations we were having in class, and they could write in the same way they wrote on social media sites. I envisioned a free flowing forum of ideas and enthusiasm, a place for authentic voices like I’d seen on Facebook and Myspace, like I’d heard in my classroom. Yeah, I was wrong.

Several years ago, I went in search of an audience for my students, although at the time I didn’t know that was what I was up to. I’d seen enough student writing to know I wasn’t doing something right in my instruction. My students were smart, interesting and capable of all manner of argument, but their writing didn’t reflect that. However, they were willing to risk suspension by breaking through the district’s internet firewall to reach sites like Myspace and Facebook where they wrote (Wrote!) about things they cared about in ways that reflected their personalities. This was what I was looking for. So I started a website where my students and I could build on the conversations we were having in class, and they could write in the same way they wrote on social media sites. I envisioned a free flowing forum of ideas and enthusiasm, a place for authentic voices like I’d seen on Facebook and Myspace, like I’d heard in my classroom. Yeah, I was wrong.

Our website quickly became a place where my ideas went to die, or where students would respond to my prompts as if they were short answer questions, writing in a dull, mechanical, and predictable way. I asked for modern examples of Holden Caulfield thinking I’d inspire students to write about alienation but got lists of “bad boy” actors and links to a band called “Holden Caulfield.” In my students’ defense, that’s how I wrote the prompts. They were prescriptive and came from my ideas about what the students should find engaging. Every now and then we’d spark a little discussion–but not really. The site was more of a bulletin board than a forum. Still, I was determined to use this new internet realm for something.

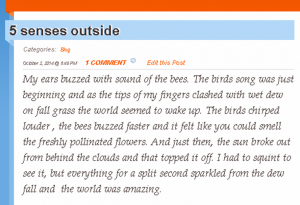

This all happened at the turn of the century, but the idea of 21st century literacy wasn’t on my radar. I wasn’t thinking about how drastically teaching reading and writing was going to be impacted by the World Wide Web. I just wanted to be in on what was happening. Though my first failures did send me in a new direction. My students were using platforms like MySpace to say things about themselves, to give their opinions, and to challenge each others’ ideas. It was entirely social, but what they were doing was writing, sometimes with letters and words, sometimes with images. But it’s all text, and that’s what drew me in. So I tried again.

This all happened at the turn of the century, but the idea of 21st century literacy wasn’t on my radar. I wasn’t thinking about how drastically teaching reading and writing was going to be impacted by the World Wide Web. I just wanted to be in on what was happening. Though my first failures did send me in a new direction. My students were using platforms like MySpace to say things about themselves, to give their opinions, and to challenge each others’ ideas. It was entirely social, but what they were doing was writing, sometimes with letters and words, sometimes with images. But it’s all text, and that’s what drew me in. So I tried again.

Dipping my educational toe into social media in a few places didn’t bring much success. Individual blogs I had my students set up felt isolated and formal. I gave them assignments to be completed on the blog, which they treated like electronic paper. The writing didn’t change much, but they were more careful and deliberate with their work. Discussion boards or chat rooms were too fast and too informal. They were conversational in nature and didn’t leave my students time for a carefully considered response. They had to get ideas out quickly or be left behind. Still, I had little glimpses of what I was after: a sustained and thoughtful conversation in writing and images. But when this occurred, I didn’t know why. I didn’t know how to recreate it.

What was the difference between what I was doing and what I wanted? The answer is audience. I hadn’t been aware of just how much weight audience carries. When I was the audience, even the perceived audience, it changed  the way my students wrote. Their voices faded. Those few times I did manage to spark something good–thoughtful, honest writing with authentic voices about a text we were looking at–then their writing became self supporting. Students abandoned me as audience and wrote for each other, fed off each other and it had very little–actually nothing–to do with me. In fact, I was very careful not to enter into the conversation because as soon as I said anything, their writing changed course and was directed at replicating the thing I’d praised. The writing even changed when students knew that I was lurking but not writing anything. Many of them would lose the nerve to be the writers they really were. It didn’t matter that I told them that their audience was each other; my mere virtual presence changed how they wrote. When I became their audience, they tried to write like students. But when their audience was other students, they wrote like writers. They had more confidence, took risks, and tried to engage the each other. In short, they did what writers do.

the way my students wrote. Their voices faded. Those few times I did manage to spark something good–thoughtful, honest writing with authentic voices about a text we were looking at–then their writing became self supporting. Students abandoned me as audience and wrote for each other, fed off each other and it had very little–actually nothing–to do with me. In fact, I was very careful not to enter into the conversation because as soon as I said anything, their writing changed course and was directed at replicating the thing I’d praised. The writing even changed when students knew that I was lurking but not writing anything. Many of them would lose the nerve to be the writers they really were. It didn’t matter that I told them that their audience was each other; my mere virtual presence changed how they wrote. When I became their audience, they tried to write like students. But when their audience was other students, they wrote like writers. They had more confidence, took risks, and tried to engage the each other. In short, they did what writers do.

Encouraged but still confused, I went looking for a platform that allows the immediacy of a conversation but encouraged more thoughtful and deliberate writing. A couple of years ago I came upon Tumblr.com. At the time, it was a kind of hybrid hipster blog with lots of art and music. There was plenty of careless writing, but there were also blogs with very good, clearly professional writing. I started by following blogs on Tumblr that both interested me and fit with what I wanted the students to see like Blake Gopnik On Art, The Paris Review , The Nearsighted Monkey. These blogs are all clearly written for a specific audience–Tumblr users–and decidedly too cool for most of my students and their teacher. That’s was part of what I was looking for. I wanted to connect my students to a fairly sophisticated audience in hopes that they might adopt the characteristics of that audience. (I was wrong about that but not for the reason I thought. That’s grist for another post.) Tumblr looked promising enough to try, so I set my first class loose.

I traditionally assigned some kind of evaluative essay where the students had to make a case for including something in the curriculum or extolling the virtues of a new technology. It was an okay assignment. It let us look at different ways to advance an argument, what counts as evidence, warrants–all of the things I wanted my students to learn. The essays were fine but lacked passion and voice because they weren’t writing about anything they really cared about, and they weren’t writing to anyone they cared about. It was an exercise to them, nothing more. Why work hard when they didn’t care about the subject or the audience?

With this question in mind, I asked student to find examples of and talk about what they thought was art (hanna art, animation). And I turned them loose in the Tumblr world. They followed, promoted and wrote about things they liked. Things they were interested in. As I watched voices emerged, I learned what my students were interested in and why they liked what they liked. I saw arguments. I saw rhetoric in action. I saw some real writing and I heard authentic student voices.

Why did Tumblr work? The audience had changed. Students were writing for themselves and trying to write in ways that would attract attention from other writers and readers in that world. This was three years ago, and I was just starting to think about how the ways that students will read and write is fundamentally different than how I read and write thanks to the new media world. That first year I took what my students did on their Tumblr blogs and kind of wedged it into an existing curricular format. It wasn’t a great fit and moving from the blogs to an essay cost them some voice, or the tone was too casual for the classroom. I didn’t do a good job of explaining how a change in audience or situation, let alone both, required some serious rethinking of rhetorical strategies. It’s an ongoing conversation I have with my students. We talk about…

- What are the characteristics of the platform and how do we adapt our writing to fit its conventions?

- Is the platform the same as the audience?

- What counts as evidence in a setting that seems to demand visual arguments?

- How do we warrant and cite a picture? A video? A gif?

- How can I make my writing stand out?

- How do I grab the audience’s attention and then hold it long enough to engage them in my writing?

- What kinds of arguments hold sway with this audience?

These are all very good, important questions that deserve serious consideration. I can’t answer them now. I usually turn the questions back at my students. They are the experts, the digital natives whose interest drew me into this world in first place. I have 20th century knowledge. They have 21st century experience.

I have only just begun to really consider what students writing in the 21st century might require of me as a teacher. It is exciting and a hot mess. How do I manage all of this? Evaluate it? Channel it? The Tumblr experiment continues into it’s third year. I’m a little more sure of what I’m doing–a little. In my next posts, I’ll share more about what’s going on–successes, failures and everything I learn.

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

The students are also independently establishing an important aspect of my classroom culture: collaboration. While I was unable to doctor the groups as much as I would have liked, the self selection told me which students could handle working with their friends and which couldn’t. I was sure to assign them a weighty task, which forced them to consider whether they could risk spending the hour socializing. It also told me where my classroom cliques were, which informed my seating choices on days when students didn’t self-select.

The students are also independently establishing an important aspect of my classroom culture: collaboration. While I was unable to doctor the groups as much as I would have liked, the self selection told me which students could handle working with their friends and which couldn’t. I was sure to assign them a weighty task, which forced them to consider whether they could risk spending the hour socializing. It also told me where my classroom cliques were, which informed my seating choices on days when students didn’t self-select.

This moment is different from the beginning of school, when everyone is excited to be back. This moment happens after my sixth grade students start to remember that:

This moment is different from the beginning of school, when everyone is excited to be back. This moment happens after my sixth grade students start to remember that: Then it happens. It is like the compact florescent lamps (CFLs). You know, the energy efficient bulb that turns on and takes a minute to become its brightest self. The light coming toward me gets brighter… (As you read this, you may think one of two things is about to happen – I am going to be wonderfully surprised or run over by that train.) The light gets brighter and brighter and suddenly, guess what? The lights are bright all over the classroom! Even Mayze, Dion, Ann, and George are completely engaged and the air in the room shifts.

Then it happens. It is like the compact florescent lamps (CFLs). You know, the energy efficient bulb that turns on and takes a minute to become its brightest self. The light coming toward me gets brighter… (As you read this, you may think one of two things is about to happen – I am going to be wonderfully surprised or run over by that train.) The light gets brighter and brighter and suddenly, guess what? The lights are bright all over the classroom! Even Mayze, Dion, Ann, and George are completely engaged and the air in the room shifts. I breathe a sigh of relief that it was not a train, but rather brains becoming adjusted to thinking and considering and probing and analyzing. The air becomes full of questions and hypotheses. Understanding and synthesizing information becomes the order of the day. New ideas, new connections. Oh my! Light bulbs start turning on all over the room. I breathe in this creative air and in my head I scream “Yes!”

I breathe a sigh of relief that it was not a train, but rather brains becoming adjusted to thinking and considering and probing and analyzing. The air becomes full of questions and hypotheses. Understanding and synthesizing information becomes the order of the day. New ideas, new connections. Oh my! Light bulbs start turning on all over the room. I breathe in this creative air and in my head I scream “Yes!” Marcia Bonds is a 6th Grade Math and English Language Arts Teacher at Key School in the Oak Park School District. She has been teaching for 17 years. Marcia is a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

Marcia Bonds is a 6th Grade Math and English Language Arts Teacher at Key School in the Oak Park School District. She has been teaching for 17 years. Marcia is a member of the Core Leadership Team of the  Engagement–what does it mean? How do we foster engagement in our classrooms? Like Marcia, I see learner identity as a key part of engaging learners. The idea of mindset playing a role in how a learner engages is well

Engagement–what does it mean? How do we foster engagement in our classrooms? Like Marcia, I see learner identity as a key part of engaging learners. The idea of mindset playing a role in how a learner engages is well  Not long ago, I came across Staci Hurst’s

Not long ago, I came across Staci Hurst’s

Susan Wilson-Golab joined Oakland Schools in 2010 following 22 years of in the field 6-12 experience across two different states and rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Her research and practice focus heavily on the evolving definition of literacy, developmental learning progressions, and formative assessment. At the district level, Susan has served as classroom teacher, Literacy Specialist, and ELA Curriculum Coordinator. These experiences and study helped Susan in her role as Project Leader for developing a

Susan Wilson-Golab joined Oakland Schools in 2010 following 22 years of in the field 6-12 experience across two different states and rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Her research and practice focus heavily on the evolving definition of literacy, developmental learning progressions, and formative assessment. At the district level, Susan has served as classroom teacher, Literacy Specialist, and ELA Curriculum Coordinator. These experiences and study helped Susan in her role as Project Leader for developing a  As teachers, we all have students who are compliant and willful, who will readily produce whatever output we ask or demand of them to please the teacher or earn a desired grade. There is no question that narrative and non-fiction writing are critical skills that must be taught explicitly at all levels every year. Increasingly, however, in an era of online publishing and digital content production on social media sites, students need to know that whatever they are asked to generate will have a meaningful audience and make a difference to someone. In 2014, kids have never known a world where they haven’t been able to reach out around the globe in seconds and make an impact with words, pictures, and video on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook. The ability to publish at the click of a button has provided a liberating opportunity for students to receive swift feedback and effectively measure the impact their writing has on their intended audience.

As teachers, we all have students who are compliant and willful, who will readily produce whatever output we ask or demand of them to please the teacher or earn a desired grade. There is no question that narrative and non-fiction writing are critical skills that must be taught explicitly at all levels every year. Increasingly, however, in an era of online publishing and digital content production on social media sites, students need to know that whatever they are asked to generate will have a meaningful audience and make a difference to someone. In 2014, kids have never known a world where they haven’t been able to reach out around the globe in seconds and make an impact with words, pictures, and video on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook. The ability to publish at the click of a button has provided a liberating opportunity for students to receive swift feedback and effectively measure the impact their writing has on their intended audience. We all know that technology tools are constantly evolving and changing. What will remain immutable, however, is the architecture of story–problem, solution, characters, and setting. As long as we enable our students to make choices about the multi-modal output they would like to try, they will be motivated to learn the fundamental writing skills they need to grow and develop as writers. Students are empowered by both multi-media tools and the allure of a wider audience. Their work will have meaning for the maximum number of people possible, as it should. Kids care about writing and creating when they know people pay attention to and care about their work, that their writerly voices will be heard.

We all know that technology tools are constantly evolving and changing. What will remain immutable, however, is the architecture of story–problem, solution, characters, and setting. As long as we enable our students to make choices about the multi-modal output they would like to try, they will be motivated to learn the fundamental writing skills they need to grow and develop as writers. Students are empowered by both multi-media tools and the allure of a wider audience. Their work will have meaning for the maximum number of people possible, as it should. Kids care about writing and creating when they know people pay attention to and care about their work, that their writerly voices will be heard.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.  We’re about four weeks into a new school year, and although I ended the summer refreshed and excited for the coming year, I also feel like I never left. I spent this summer immersed in professional learning that came in many forms: presenting at conferences, attending workshops, and reading–nine books total, eight of them professional. One of the books I read (on an airplane, en route to Florida) was Kate Roberts’ and Chris Lehman’s

We’re about four weeks into a new school year, and although I ended the summer refreshed and excited for the coming year, I also feel like I never left. I spent this summer immersed in professional learning that came in many forms: presenting at conferences, attending workshops, and reading–nine books total, eight of them professional. One of the books I read (on an airplane, en route to Florida) was Kate Roberts’ and Chris Lehman’s

Jianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a

Jianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a  Current research surrounding literacy for students with significant disabilities has demonstrated that, with appropriate support and instruction, all students can be readers and writers. Traditionally, the approach has been a readiness model stating that literacy should be learned in a pre-determined, sequential manner that requires certain skills to be in place before the student can advance to the next level. The rigidity of this model has created barriers that many of our students can not overcome. The current view on literacy learning, however, focuses on enhancing communication and language opportunities to help students make connections and learn to use print in a meaningful way.

Current research surrounding literacy for students with significant disabilities has demonstrated that, with appropriate support and instruction, all students can be readers and writers. Traditionally, the approach has been a readiness model stating that literacy should be learned in a pre-determined, sequential manner that requires certain skills to be in place before the student can advance to the next level. The rigidity of this model has created barriers that many of our students can not overcome. The current view on literacy learning, however, focuses on enhancing communication and language opportunities to help students make connections and learn to use print in a meaningful way.