Last year I participated in a book study at the Oakland Schools chapter of the National Writing Project. It picked up themes from a summer workshop on creating a culturally responsive classroom. Focused on Geneva Gay’s book, it began for me a difficult process that, along with a conversation I had with my seniors, taught me that I wasn’t doing enough to create a classroom atmosphere that promoted and supported all of my students equally.

Last year I participated in a book study at the Oakland Schools chapter of the National Writing Project. It picked up themes from a summer workshop on creating a culturally responsive classroom. Focused on Geneva Gay’s book, it began for me a difficult process that, along with a conversation I had with my seniors, taught me that I wasn’t doing enough to create a classroom atmosphere that promoted and supported all of my students equally.

During this conversation–a kind of exit interview I’ve done on and off over the years–my students of color gave me some hard facts about the education I was trying to help them with. They said that they were “used to” being on the outside, used to only reading about white people–except in February–that that’s just how it is.

Used to it.

That haunts me.

Blind to the problems I was creating and perpetuating, I decided to ask myself hard questions about my own assumptions, and how those assumptions were affecting my students. I don’t like the answers I’m getting but I’m going to work on it.

Step 1: Expand Our Horizons

Step 1: Expand Our Horizons

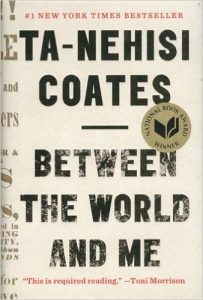

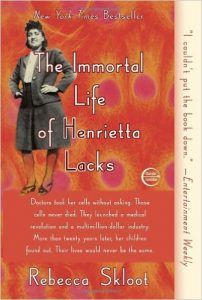

Over the summer I assigned The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and Between the World and Me to my AP Language and Composition classes.

We read Lacks last year, and I thought that by adding Coates’ excellent book to the menu, I might begin to open my students’ thoughts to ideas of privilege, to a culture that sends very different messages to students who lie outside the mainstream. I’ve come to see summer reading as an opportunity to introduce students to things they might not pick up and that are not from the canon.

Step 2: Brave Conversations and Listening

I edged students into the shallow end of this conversation about race, exploitation, poverty, and history by using a Culture of Thinking routine–Circle of Viewpoints. This let us take on different points of view and explore how the writer can skillfully move a reader through complicated and difficult ideas.

My hope was that this would set the tone for the more challenging Between the World and Me. For this I used a simple Think-Pair-Share routine to set up small conversations that I could eavesdrop on. With students spread out all over the floor, their books open to close-read passages, I watched and listened. How would they respond to Coates’ razor sharp, often accusatory, observations? Most of my students are people who “think they’re white,” but there’s a sizable portion who are not. Avondale is blessed with a remarkably diverse population. Would the white students notice the knowing looks on their non-white classmates’ faces, as they read passages that pointed to a culture that told them that they were “different”? How would they react to the idea that there are laws and regulations that are not just unfairly enforced, but designed to put certain groups of people on the wrong side of them?

Another Step: Reflect

It was a mixed result. I didn’t expect an epiphany about privilege. Epiphanies are rare, and scary. My aim was to point students toward challenging ideas, those that were skillfully written.

Some of the ideas were too much for them–my fault for not better scaffolding the skills–but there were some encouraging conversations. I heard a conversation connecting Coates’ idea about the “control of black bodies” to what happened to Henrietta Lacks’ cells. In another conversation in a larger group, students discussed how the dress code seemed to be designed to make girls’ fashion choices responsible for boys’ behavioral ones. I heard students wonder about the dress code’s prohibition against “sagging” and who that might be aimed at.

These are tough issues. But when I feel that discomfort, I think back to that conversation last May and that horrible phrase “used to it,” that my students felt like outsiders, extras in a play not about them. That discomfort we feel, that shift from familiar to unknown–that seems important enough to spend time on, and I’ll be returning to it throughout the year.

Always Another Step

I’d like to invite others to help me with this. I’ll take any advice, and I’d love to talk about these issues. The book study ended so I’ve got some time.

Who’s up for some discomfort?

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

This is the third time I’ve rewritten this opening.

This is the third time I’ve rewritten this opening.  In my classes, we talk a lot about using precise language that gives you the most bang for your buck. Twitter forces that because you only have 140 characters. The day after the protests in Charlotte, NC, this fall, we talked about word choice and how it sends implicit messages. One example:

In my classes, we talk a lot about using precise language that gives you the most bang for your buck. Twitter forces that because you only have 140 characters. The day after the protests in Charlotte, NC, this fall, we talked about word choice and how it sends implicit messages. One example:  Hattie Maguire (

Hattie Maguire (

Amy Gurney (

Amy Gurney ( One of the cool things about teaching is that each year is a new season. After all the reflecting and conversations about what worked and what didn’t, we get to design new plans and start fresh in September.

One of the cool things about teaching is that each year is a new season. After all the reflecting and conversations about what worked and what didn’t, we get to design new plans and start fresh in September. That spark from Corey’s offer helped me come up with a new plan. I’m calling it HerodotusHive.

That spark from Corey’s offer helped me come up with a new plan. I’m calling it HerodotusHive. Rod Franchi (

Rod Franchi ( Each year, students tell me, “I don’t read” or “I haven’t read a whole book since the fourth grade.” I take those comments as a challenge. It’s part of who I am. If someone tells me that something can’t be done, I double down and whisper to myself, “Wanna bet?”

Each year, students tell me, “I don’t read” or “I haven’t read a whole book since the fourth grade.” I take those comments as a challenge. It’s part of who I am. If someone tells me that something can’t be done, I double down and whisper to myself, “Wanna bet?”

Megan Kortlandt (

Megan Kortlandt (

Caroline Thompson (

Caroline Thompson (

Rick Joseph (

Rick Joseph ( Over the summer, the literacy researcher

Over the summer, the literacy researcher  I am an avid practitioner of yoga, and often my yoga teachers will tell the class to stay in the pose, to give it some “hang time” before we move onto the next pose. That’s the hard part, though. When it’s hard and you want to get out, that’s where the work happens. The same is true when talking about data–the power is in our ability to give ourselves intellectual “hang time.”

I am an avid practitioner of yoga, and often my yoga teachers will tell the class to stay in the pose, to give it some “hang time” before we move onto the next pose. That’s the hard part, though. When it’s hard and you want to get out, that’s where the work happens. The same is true when talking about data–the power is in our ability to give ourselves intellectual “hang time.” Jianna Taylor (

Jianna Taylor ( Young adult (YA) literature often gets a bad rap. As a high school librarian, I hear the worst of the stereotypes often. One of the most common is that YA literature is too “dark” or “heavy” or “moody.” I find this perspective perplexing.

Young adult (YA) literature often gets a bad rap. As a high school librarian, I hear the worst of the stereotypes often. One of the most common is that YA literature is too “dark” or “heavy” or “moody.” I find this perspective perplexing. Bethany Bratney (

Bethany Bratney (