Note: This post was originally published on April 11, 2018, on ASCD’s inService Blog.

Every student in every classroom has a voice. Students’ voices come from their understanding of who they are, in what they believe, and why they have these beliefs. Within the context of education, student voice can be broadly defined as individual perspectives and actions of learners.

We believe that bringing out student voice is not a one-time happening; rather, it is a process, in which we, educators, need to carefully guide our students. Student voice is deeply connected to children’s understanding of who they are as individual beings. Because of this, nurturing student voice requires adult attention on many levels, including personal, academic, and social. There are three main areas of teaching that need to align in order for students to feel empowered to discover and share their voices: learning spaces, teaching strategies, and assessments.

1. Creating Physical Spaces that Promote Student Voice

Student voice is increasingly being considered a vital component of shared decision-making in secondary classrooms. If we truly believe in the value of students as co-designers of their learning, we first have to listen to their voice through giving them choices within the physical environment of a classroom.

The layout of furniture and learning tools should be determined by the anticipated types of learning and individual students’ needs: room for collaboration, conferencing, small groups, anchor charts, norms, mentors/models, student charting, and even separate independent practice space.

As the year unfolds and students have experienced various seating arrangements, offer them the opportunity to choose their own settings. For example, students understand that collaboration is an important aspect of our class so about half of the tables are arranged into groups of four to six students. Why only half? Because when asked, some students expressed that sitting in a collaborative group is distracting when working independently or during direct instruction. Students advocated for some of our tables to stay in a group of two or face toward our large window.

A growing population of students also seems to be performing better if afforded movement, including standing during the class period. Thus, a standing table was incorporated into our classroom. In addition, a low table with legless swivel chairs is available to students who need room to stretch out and move without distracting others.

Not only does asking students to be co-designers of their physical environment promote shared decision-making, but it also invites them to reflect on themselves as learners.

2. Choosing Strategies and Projects that Help Students Find Their Voice

Creating learning experiences that connect to real life opportunities, student interests, and authentic audiences can ignite voice, choice, and ultimately, learning. There are endless ways to incorporate such experiences in our classrooms.

This year, instead of starting the new calendar year with drafting extensive New Year’s resolutions, students engaged in the #OneWord2018 project to express in one word what mattered to them in 2018: a single virtue, challenge to overcome, or passion. They viewed a clip from The Today Show about stamped washer bracelets created by jewelry maker Chris Pan, searched the trending hashtag, and considered how their #OneWord might impact their lives and lives of those around them. Students had the opportunity to craft a washer bracelet as a daily reminder of their goal; many of them added to the trending Twitter hashtag.

Another example of an assignment that promotes student voice and choice and can be used in a number of settings is the Storytelling project, originally done in a college freshman composition class. With the premise that every person has a story and can teach us a valuable lesson, students were to tell a compelling story about an average person in their life. They were given a choice to interview anyone they desired through the lenses of discovering one important experience that shaped this person in who she or he was today. Students had to create their own questions, schedule interviews, take notes or record their conversations, create a verbal sketch of their subject, and finally, write a profile featuring the person and his or her story. At the end, they were to share their stories with their subjects and receive feedback. This project gave students a lot of freedom to think and be creative with their own story. More importantly, it gave them an opportunity to figure out why their person matters and share their voices. This project was also impactful in the way that it created bonds between people and brought valuable perspectives to both interviewers and interviewees.

Any opportunity students have to share their ideas outside of our classroom walls grows their understanding that not only do their words matter, but that we, educators, believe that their words can make a difference. Encouraging students to submit writing to contests, newspapers, magazines and, when possible, inviting parents and community members in as an authentic audience are all ways to show the importance of student voice. Depending on the assignment, visitors may simply serve as listening ears; other times, they may be able to offer valuable feedback about students’ creative ideas, book recommendations, business plans, writing, presentation skills, and other aspects of student work.

3. Redesigning Grading and Assessments to Encourage Student Ownership of Their Work

How we approach grading student work tells them a lot about what matters in our classrooms. There are two areas that we need to consider if we wish to show students that their voice is important: making students part of their own assessments and shifting the focus from grading the final output to assessing the entire work that goes in a specific project or assignment.

Making students part of their own assessments

Involving students in determining what skills should be assessed and how they should be measured is one way to promote student voice. In a 7th grade Language Arts classroom, students examined several versions of one particular assignment: some were exemplars, while others exhibited beginning and developing skills. Students determined how closely each example met the task, as well as strengths and shortcomings of each one. Based on these noticings, small groups brainstormed components and skills that should be present within the task and assessed on the rubric. Students came together as a whole class to compare drafted rubrics, make compromises, merge, revise and even delete some components. In the end, the process captured each student’s ideas, as well as deepened their understanding of a specific genre.

Students’ choices are also important in selecting how they can best communicate their understanding of the topic or task. Giving students the option of a written task, constructing a piece of art, or creating a project using technology highlights student strengths and passions.

Assessing the entire work that goes in a specific projects

To continue the example of the Storytelling Project, the entire preparatory work that went into writing a profile was assessed along with the final essay. To put more emphasis on the process of voice discovery, students were to produce a Profile Portfolio, which consisted of interview questions and notes, sketch notes, first and final drafts, and students’ own input in their assessment–their end-of the-project reflection. Every component was worth a specific amount of points, and omitting one would mean a lower grade.

After sharing their writing with their profiled person, students reflected on the meaning of this project and writing process to them as writers. A quote from one student’s reflection captures the discovery: “My grandpa and I had a lot of fun doing this journalistic writing project. Yet, he did not help me write it sitting by the computer; he did help me write it in word. His words were powerful to me. We both learned a lot. He learned that his words can be sent down to other generations and then permeated throughout the world. No matter if it is on paper or not. I learned that a story isn’t just a story. It depends on what one wants to see in it.”

In a strategic environment, teachers afford students opportunities to choose where and how they work, interact with one another, share, reflect and document their thinking. As a result, students simultaneously develop their subject-specific know-how and form better knowledge of who they are as learners and individuals.

Arina Bokas, Ph.D., is the editor of Kids’ Standard Magazine and a writing instructor at Mott Community College, Flint, Michigan. She is the author of Building Powerful Learning Environments: From Schools to Communities. Connect with Bokas on Twitter.

Monica Phillips is a Language Arts teacher and ELA Department Chair at Sashabaw Middle School in Clarkston, Michigan. She also serves as a Professional Learning Community coordinator and facilitator for secondary teachers in her district. Connect with Phillips on Twitter.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters in English Education from Eastern Michigan University. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions. When she’s not teaching, Lauren often runs for the woods with her husband and their three sons/Jedi in training and posts many stylized pictures of trees on Instagram.

Lauren Nizol (@CoachNizol) is an MTSS Student Support Coach and Interventionist at Novi High School. She has eleven years of classroom experience, teaching English, IB Theory of Knowledge and English Lab. Lauren completed her undergraduate degree in History, English and Secondary Education at the University of Michigan-Dearborn and her Masters in English Education from Eastern Michigan University. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant with the Eastern Michigan Writing Project and an advocate for underperforming students and literacy interventions. When she’s not teaching, Lauren often runs for the woods with her husband and their three sons/Jedi in training and posts many stylized pictures of trees on Instagram.

Michael Ziegler (

Michael Ziegler (

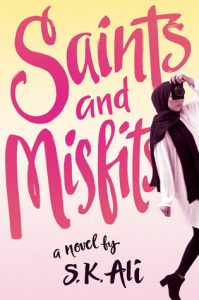

Saints and Misfits, by S.K. Ali (Morris Finalist)

Saints and Misfits, by S.K. Ali (Morris Finalist) Bethany Bratney

Bethany Bratney

Hattie Maguire (

Hattie Maguire (