This is part 2 in a series. Here’s part 1, The Importance of Joy.

There is a video I like to play when I facilitate professional development. It’s about a blind man trying unsuccessfully to beg for money on a city street. Passersby rarely give him a coin and mostly ignore him. One woman walks past him, then thinks better of it and turns around. She proceeds to change what is written on his sign from “I’m blind, please help me,” to “It’s a beautiful day, and I can’t see it.”

Almost immediately, the people passing by are much more likely to give him a few coins. The woman comes back later, and the blind man asks her what she wrote. She responds with, “I wrote the same but in different words.”

Now, full disclosure, this video is an ad for a company, but the message is the same: the words we use are powerful and have the ability to change our worlds.

Part of What Stunts Change

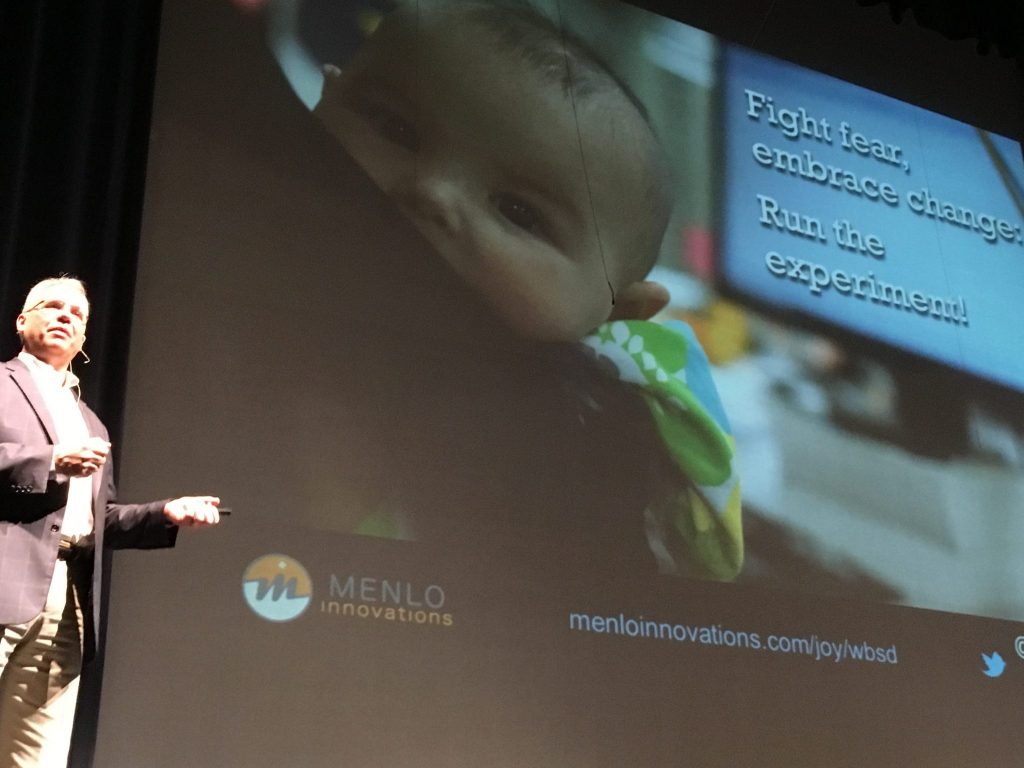

Recently, we had the pleasure of bringing Richard Sheridan, CEO of Menlo Innovations, to West Bloomfield as the keynote speaker for our district-wide professional development. Sheridan wrote a book called Joy, Inc., which details Menlo Innovations’ journey to build joy into every facet of their company culture. After reading Joy, Inc., we knew that Sheridan’s message would be a powerful one for our staff.

As Sheridan spoke, there were so many meaningful takeaways. But the one that resonated most with me and many others was his mantra to “Fight fear, embrace change: run the experiment!”

So often, fear paralyzes us, especially in education. As teachers, we’re so cautious to embrace change because we’ve had so many bad experiences with change: it’s not funded, we’re not trained, administrators don’t value it, we know it’s going to change again in a year–this list goes on endlessly. Sheridan encourages us to try new things anyway, maybe even in spite of our fear.

In West Bloomfield, we are in the middle of figuring out what 21st-century learning looks and feels like, and have had many conversations about flexible furnishing and spaces. David Stubbs, creator of Cultural Shift, an independent consulting company that stimulates design thinking, has been working with us on these endeavors.

In a meeting with him recently, we were lamenting the fact that many teachers say something to the effect of “that’s great, but…” and give myriad reasons why the idea wouldn’t work. Stubbs urged us to turn the conversation on its head, to ask another question instead:

But What Happens if We Do It?

In a time when we consider every possibility for why something won’t work, what happens if we run the experiment and do the thing we think will never work?

When we continually focus on why something won’t work, we never allow our minds to imagine that thing actually working, and thus limit our capacity for making change.

When I think about saying the same thing but with different words, like the woman in the video, I can’t help but think about how we can change our outlook with the change of one word. What if, instead of saying “but,” we said “and”? What if the teachers mentioned earlier said, “That’s great, and….” And rather than giving reasons why it wouldn’t work, they gave reasons why it would?

What would happen if we just did it?

Jianna Taylor (@JiannaTaylor) is the ELA Curriculum Coordinator for the West Bloomfield School District. Prior to this role, she was a middle school ELA and Title 1 teacher. She is a MiELA Network Summer Institute facilitator and is an Oakland Writing Project Teacher Leader. Jianna earned her bachelor’s degree from Oakland University and her master’s degree from the University of Michigan. She also writes reviews of children’s books and young adult novels for the magazine School Library Connection.

Jianna Taylor (@JiannaTaylor) is the ELA Curriculum Coordinator for the West Bloomfield School District. Prior to this role, she was a middle school ELA and Title 1 teacher. She is a MiELA Network Summer Institute facilitator and is an Oakland Writing Project Teacher Leader. Jianna earned her bachelor’s degree from Oakland University and her master’s degree from the University of Michigan. She also writes reviews of children’s books and young adult novels for the magazine School Library Connection.

I don’t generally read “business model” type books, but when one of our Board of Education members

I don’t generally read “business model” type books, but when one of our Board of Education members  With test prep season beginning and the M-STEP looming, teachers can become frustrated because there are not many

With test prep season beginning and the M-STEP looming, teachers can become frustrated because there are not many

Over the summer, the literacy researcher

Over the summer, the literacy researcher  I am an avid practitioner of yoga, and often my yoga teachers will tell the class to stay in the pose, to give it some “hang time” before we move onto the next pose. That’s the hard part, though. When it’s hard and you want to get out, that’s where the work happens. The same is true when talking about data–the power is in our ability to give ourselves intellectual “hang time.”

I am an avid practitioner of yoga, and often my yoga teachers will tell the class to stay in the pose, to give it some “hang time” before we move onto the next pose. That’s the hard part, though. When it’s hard and you want to get out, that’s where the work happens. The same is true when talking about data–the power is in our ability to give ourselves intellectual “hang time.” Jianna Taylor (

Jianna Taylor (

A few months back,

A few months back,

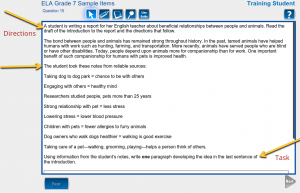

Recently, I facilitated a webinar about preparing students for the ELA M-STEP. (You can access a

Recently, I facilitated a webinar about preparing students for the ELA M-STEP. (You can access a

During the second half of the school year, I opened my classroom up to a doctoral student from the University of Michigan who was studying what untaught and sometimes intangible things make teachers successful. It was a wonderful experience, and I learned a lot about myself as a teacher through the reflective nature of the process. As compensation for my time and energy, I was presented with a $100 gift card for Amazon. I knew exactly what I would buy: books! One book, in particular, was on my wish list, Jennifer Serravallo’s

During the second half of the school year, I opened my classroom up to a doctoral student from the University of Michigan who was studying what untaught and sometimes intangible things make teachers successful. It was a wonderful experience, and I learned a lot about myself as a teacher through the reflective nature of the process. As compensation for my time and energy, I was presented with a $100 gift card for Amazon. I knew exactly what I would buy: books! One book, in particular, was on my wish list, Jennifer Serravallo’s