Anyone who knows me knows that I am a voracious reader (comes with the English teacher territory, right?). Anyone who knows me really well knows that I’m not just reading books for pleasure, but that I’m a voracious reader of professional books. Case in point: I read five books about grading last summer. Riveting stuff.

Anyone who knows me knows that I am a voracious reader (comes with the English teacher territory, right?). Anyone who knows me really well knows that I’m not just reading books for pleasure, but that I’m a voracious reader of professional books. Case in point: I read five books about grading last summer. Riveting stuff.

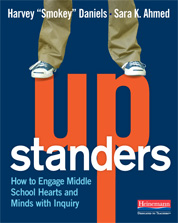

A few months back, a colleague from the MiELA Network conference suggested I read the book Upstanders because it might help with my conference session this summer. The title and back cover information intrigued me, so I immediately ordered the book and awaited its arrival. My reading rate during the school year is definitely much slower than during the summer because there is so much else I have to do, but by any standard, I devoured Upstanders.

Of all of the professional books I have read, this is the first that felt as if it were written directly for me and the type of teacher I am. I could see myself as a teacher in the pages, but more than that, I could see a better version of my teacher self in the pages. I felt like I had a model of the type of teacher I want to be that wasn’t a huge leap from where I already am. Many times when I’m reading a professional book, I’ll want to do something the way the authors do, but I’ll know that that isn’t me or that the change seems too overwhelming, which leads me to not change at all. I was so enamored with this book that I tweeted at and sent emails to the authors–and they responded!

Upstanders is written as a collaboration between Daniels and Ahmed and offers a glimpse into the workings of Ahmed’s classroom, since she is still a practicing teacher. As the title would suggest, inquiry is a hallmark of Ahmed’s classroom, so I decided to try out some of her and Daniels’ ideas. To get her students engaged in inquiry work consistently, she has them involved in “mini-inquiries,” which are “quick exercise[s] in honoring our curiosity and finding out information about things that puzzle us in the world” (106). Mini-inquiries can take anywhere from a few minutes to a class period to complete, as they are supposed to be what the name suggests: mini. Sometimes Ahmed’s students are looking into a topic she suggested or a topic that grew out of a class discussion. Other times, students are researching something they are interested in finding out more about. I really liked this idea and wanted to incorporate it into my practice, but I worried about taking time away from our already packed curriculum. As the authors suggested, though, a great way to try a mini-inquiry is on one of those days right before a break where you’ve finished a unit but don’t want to start another one. So the day before mid-winter break, I found myself with the perfect opportunity to try a mini-inquiry.

Upstanders is written as a collaboration between Daniels and Ahmed and offers a glimpse into the workings of Ahmed’s classroom, since she is still a practicing teacher. As the title would suggest, inquiry is a hallmark of Ahmed’s classroom, so I decided to try out some of her and Daniels’ ideas. To get her students engaged in inquiry work consistently, she has them involved in “mini-inquiries,” which are “quick exercise[s] in honoring our curiosity and finding out information about things that puzzle us in the world” (106). Mini-inquiries can take anywhere from a few minutes to a class period to complete, as they are supposed to be what the name suggests: mini. Sometimes Ahmed’s students are looking into a topic she suggested or a topic that grew out of a class discussion. Other times, students are researching something they are interested in finding out more about. I really liked this idea and wanted to incorporate it into my practice, but I worried about taking time away from our already packed curriculum. As the authors suggested, though, a great way to try a mini-inquiry is on one of those days right before a break where you’ve finished a unit but don’t want to start another one. So the day before mid-winter break, I found myself with the perfect opportunity to try a mini-inquiry.

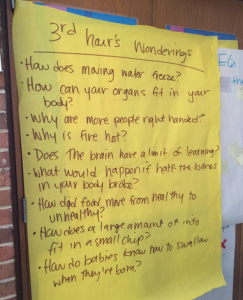

That day, I began the lesson by talking with my kids about how we were going to try something new, and that we would research the random things we’ve always wanted to know. They kind of looked at me funny, so as an example, I told them a story about how whenever I walk by this particular building in the winter, I see that the water has frozen in motion as it came out of the gutter. I always thought that I wanted to be there at the exact moment the water went from a liquid to a solid since the ice looks like a frozen waterfall. I then went on to explain that if I wanted to make this a researchable question (which we had talked about in the argument paragraph unit we had just finished), I might say, “How does moving water freeze?” I then asked students to brainstorm the things that they had always wondered but never bothered to look up or learn about. After students had talked with a partner, we created a class list of wonderings to keep up throughout the year (see the image below). Some of the wonderings are very profound and some of them are less serious, which was OK for that day’s purpose.

Once students turned their topics into research questions and I briefly modelled how I might go about looking for information related to my question, they took out their Chromebooks and began researching. After just a few minutes, hands started popping up:

“Mrs. Taylor, come LOOK at this!”

“You have to see this!”

“Can you believe this is true?!”

“That is not what I expected to find out!”

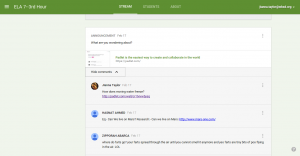

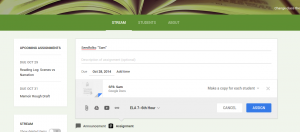

As students began finding information that related to their questions, I urged them to post it on our Google Classroom wall under the thread I had begun with my question and an article about it.

As the hour ended, many students had found some kind of answer to their question and shared with the whole class, many of them fascinated by each other’s findings. I had not anticipated this, but as I was wrapping up the hour and talking through what students had done, I noticed that within one hour, students had truly gone through the entire research process in an abbreviated form that we had spent many weeks going through with the argument paragraph. Students brainstormed topics they were interested in learning more about, created research questions, sorted through various sources on the Internet to choose good ones, and shared their learning with others.

As I envision future research projects, both this year and in the future, I can see how engaging students in mini-inquires will help pique their interest and allow them to continue to hone their research skills. This could be a great way to start a unit or allow students to learn about different topics within a unit. In fact, the Common Core asks that students be involved in short research projects throughout the year that focus specifically on creating research questions and finding information to support them (corestandards.org). Mini-inquiries could be a great way to achieve this in addition to all of their other benefits.

J ianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a MiELA Network Summer Institute facilitator and member of the OWP Core Leadership Team. Jianna earned her bachelor’s degree from Oakland University and her master’s degree from the University of Michigan. She also writes reviews of children’s books and young adult novels for the magazine Library Media Connection.

ianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a MiELA Network Summer Institute facilitator and member of the OWP Core Leadership Team. Jianna earned her bachelor’s degree from Oakland University and her master’s degree from the University of Michigan. She also writes reviews of children’s books and young adult novels for the magazine Library Media Connection.

The writer’s notebook is almost a sacred, mythical element of the writer’s workshop. It is where students’ writing lives take shape and are documented over the course of a year. In my classroom, the writer’s notebook held everything, and I mean EVERYTHING. Any paper I handed out was immediately taped or glued into the notebook, even if it had to be turned on its side or folded over two times. The writer’s notebook was our textbook. So when I heard each one of my students would be getting a Chromebook, I was excited about the possibilities and what that could mean for student writing. But what nagged at me was the loss of the traditional, tangible writer’s notebook.

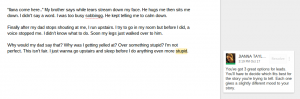

The writer’s notebook is almost a sacred, mythical element of the writer’s workshop. It is where students’ writing lives take shape and are documented over the course of a year. In my classroom, the writer’s notebook held everything, and I mean EVERYTHING. Any paper I handed out was immediately taped or glued into the notebook, even if it had to be turned on its side or folded over two times. The writer’s notebook was our textbook. So when I heard each one of my students would be getting a Chromebook, I was excited about the possibilities and what that could mean for student writing. But what nagged at me was the loss of the traditional, tangible writer’s notebook. Instead of kids bringing their notebooks to one another and reluctantly allowing a partner to write on their prized draft, kids are sharing documents with one another and setting the editing level based on their comfort, with many choosing to only allow their partners to comment on a document. They no longer have to worry that someone is going to “mess up” their paper. They can simply focus on the comments, and especially relish hitting the “Resolve” button when they have revised something. I think it’s more than just reading the comments and making changes, though; kids are having conversations via their comments about writing as well as having conversations about their writing out loud. The conversations about writing are multilayered. If you’ve ever seen a teen text and talk to someone at the same time, you know that holding multiple conversations on various platforms is a way of life. And students also seem to be more responsive to my suggestions because my comments don’t physically change their writing; they are seen as just that: comments and suggestions.

Instead of kids bringing their notebooks to one another and reluctantly allowing a partner to write on their prized draft, kids are sharing documents with one another and setting the editing level based on their comfort, with many choosing to only allow their partners to comment on a document. They no longer have to worry that someone is going to “mess up” their paper. They can simply focus on the comments, and especially relish hitting the “Resolve” button when they have revised something. I think it’s more than just reading the comments and making changes, though; kids are having conversations via their comments about writing as well as having conversations about their writing out loud. The conversations about writing are multilayered. If you’ve ever seen a teen text and talk to someone at the same time, you know that holding multiple conversations on various platforms is a way of life. And students also seem to be more responsive to my suggestions because my comments don’t physically change their writing; they are seen as just that: comments and suggestions.  I had toyed with the idea of having students use a single, running Google Doc to keep a notebook, but that doesn’t work as easily as a traditional notebook does, especially when using Google Classroom, because some of the documents would be in Classroom and some would be in the running Google Doc. I thought toggling between the two would be difficult. Obviously, no single platform seems to be perfect (it’s unlikely that anything will ever meet every need/want). Despite the misgivings I may have, my students do not seem to be having the same internal struggles that I am having. Using their Chromebooks has quickly become second nature, with the biggest complaint being that the WiFi isn’t working quickly enough!

I had toyed with the idea of having students use a single, running Google Doc to keep a notebook, but that doesn’t work as easily as a traditional notebook does, especially when using Google Classroom, because some of the documents would be in Classroom and some would be in the running Google Doc. I thought toggling between the two would be difficult. Obviously, no single platform seems to be perfect (it’s unlikely that anything will ever meet every need/want). Despite the misgivings I may have, my students do not seem to be having the same internal struggles that I am having. Using their Chromebooks has quickly become second nature, with the biggest complaint being that the WiFi isn’t working quickly enough! At the end of last year, we found out that our district, West Bloomfield, would be going

At the end of last year, we found out that our district, West Bloomfield, would be going

We’re about four weeks into a new school year, and although I ended the summer refreshed and excited for the coming year, I also feel like I never left. I spent this summer immersed in professional learning that came in many forms: presenting at conferences, attending workshops, and reading–nine books total, eight of them professional. One of the books I read (on an airplane, en route to Florida) was Kate Roberts’ and Chris Lehman’s

We’re about four weeks into a new school year, and although I ended the summer refreshed and excited for the coming year, I also feel like I never left. I spent this summer immersed in professional learning that came in many forms: presenting at conferences, attending workshops, and reading–nine books total, eight of them professional. One of the books I read (on an airplane, en route to Florida) was Kate Roberts’ and Chris Lehman’s