For the next two years, I will be part of the Galileo Leadership Consortium, which works to advance teacher leadership. In this role, I am asked to learn that I can do better for the profession.

For the next two years, I will be part of the Galileo Leadership Consortium, which works to advance teacher leadership. In this role, I am asked to learn that I can do better for the profession.

Sometimes all we have to realize is that we only have to know that we can do better. And one of the things that the consortium believes we can do better is grading. We believe that grading doesn’t have to be punitive, and that it can actually relay information about what a child has learned. To help you understand and implement these beliefs, I will share the information I have learned from experts, and how I have used that learning in my 8th grade Language Arts classroom.

Wormeli’s Views of Grading

The first expert I encountered was Rick Wormeli. He is best known for his research on 21st-century teaching practices. Five minutes into a day with him, though, and you realize that he has used all of the research that he presents.

From Wormeli, I learned three things:

- Teachers are ethically responsible for the grades which they report.

This means that grades that are padded—with scores for neatness, following directions, turning work in on time—are grades that do not represent the amount of learning the student has achieved.

- Grades should accurately report the amount of mastery that a student has on the standards of that subject.

This means that an A in Language Arts represents that the student has achieved an A level of mastery in the reading and writing of narrative, argument, and information. An A level of mastery is typically coined by the terms “Exceeding Mastery.”

- Assessments should be connected to standards.

This means that all activities that we ask of students should be related to the learning they should be achieving. So, every assessment should be connected to a standard, so the student’s grade can reflect the achievement of that standard.

What This Looks Like in My Classroom

So, what does standards-based grading mean in literacy instruction, and what does this look like in my classroom?

I don’t have a definitive answer, but I have some experiences that I will share.

Shift 1: I connect daily lessons to standards, and present these connections to students.

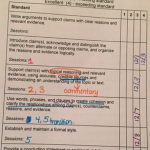

At the beginning of each lesson, I name my teaching point. Students and I refer to our Self-Evaluation Standards page (you can click on the thumbnail image to the right). On this page, we underline key words and compare how our work achieved that standard. As you can see, the columns represent achievement levels. Students can mark a date and a level they think they achieved. From here, students can see their growth towards achieving each standard.

Shift 2: For every standard that I teach to kids, I create a rubric of achievement.

I share the rubrics with kids along with exemplars (thumbnail on the right) of each achievement level. Students can see where their work aligns with that of their peers and the way work should look. The rubric and examples help kids to work to meet the standards.

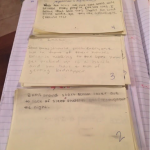

Shift 3: I insist that students walk away each day having learned something.

In order to quantify this, I have started giving quick and varied formative assessments. For one  concept, it may be a post-it of key terms, with verbal descriptive feedback. For another concept, it may be written descriptive feedback about how to move forward in achieving a standard (an example is on the right). For any assessment, students may re-try the work, in order to show more learning. This helps kids learn and apply the material, but it also shows them that they are active learners, and learners who are successful.

concept, it may be a post-it of key terms, with verbal descriptive feedback. For another concept, it may be written descriptive feedback about how to move forward in achieving a standard (an example is on the right). For any assessment, students may re-try the work, in order to show more learning. This helps kids learn and apply the material, but it also shows them that they are active learners, and learners who are successful.

Every day in my classroom looks a little different. And I am using different strategies to reach all of my learners. But in doing so, I know what standard that students have achieved and what standard they are working on. We also have a great community that wants to work and grow and show their best work. And all this came from three small shifts.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

took a deep breath. I was excited to arrive after the two hour commute on a sunny Sunday morning. To say I wasn’t nervous would be a lie. I was about to embark on what I had heard was an incredible, yet challenging week of intense learning. I, along with eight Oakland County teachers and two of my Oakland Schools colleagues, would spend the next seven days together attending a Level II course in Literacy for Students with Significant Disabilities at

took a deep breath. I was excited to arrive after the two hour commute on a sunny Sunday morning. To say I wasn’t nervous would be a lie. I was about to embark on what I had heard was an incredible, yet challenging week of intense learning. I, along with eight Oakland County teachers and two of my Oakland Schools colleagues, would spend the next seven days together attending a Level II course in Literacy for Students with Significant Disabilities at

For my first triathlon, actually my only triathlon, I swam with a snorkel. Yes, you are allowed to do so, however you can not win. Being the disciplined athlete I am I was unencumbered by this restriction as I wheezed around the course.

For my first triathlon, actually my only triathlon, I swam with a snorkel. Yes, you are allowed to do so, however you can not win. Being the disciplined athlete I am I was unencumbered by this restriction as I wheezed around the course. Swimming is challenging for me. If the swim leg of a sprint triathlon was 50 yards, I would be fine, but it is not. It is 1/2 mile, which is a long, long way for me. The ride and the run are OK; note I did not say easy, or enjoyable.

Swimming is challenging for me. If the swim leg of a sprint triathlon was 50 yards, I would be fine, but it is not. It is 1/2 mile, which is a long, long way for me. The ride and the run are OK; note I did not say easy, or enjoyable. Effective feedback, grounded in where the learner is in the moment, is critical. It would be helpful, though not always essential, to have feedback from peers and/or a more knowledgeable other. However, in the end, it is the learner’s (my) responsibility for success. Interestingly, this raises the issue of goal setting, which is something for another day.

Effective feedback, grounded in where the learner is in the moment, is critical. It would be helpful, though not always essential, to have feedback from peers and/or a more knowledgeable other. However, in the end, it is the learner’s (my) responsibility for success. Interestingly, this raises the issue of goal setting, which is something for another day. Prior to coming to Oakland Schools in 2004, Les Howard worked as an independent consultant across the United States based in San Francisco. Les came to California in 1994 to help establish Reading Recovery in California. He has been an educator for almost 40 years, almost 20 years in Australia. During this time he has been an elementary teacher, assistant principal, and literacy consultant and district literacy coordinator. Les is also a trained Ontological Coach. He believes coaching is a powerful process that empowers educators. He loves being outdoors and loves bicycling hiking, paddling, triathlons and adventure races, and trying to tire out his border collie. He and his wife enjoy traveling and camping.

Prior to coming to Oakland Schools in 2004, Les Howard worked as an independent consultant across the United States based in San Francisco. Les came to California in 1994 to help establish Reading Recovery in California. He has been an educator for almost 40 years, almost 20 years in Australia. During this time he has been an elementary teacher, assistant principal, and literacy consultant and district literacy coordinator. Les is also a trained Ontological Coach. He believes coaching is a powerful process that empowers educators. He loves being outdoors and loves bicycling hiking, paddling, triathlons and adventure races, and trying to tire out his border collie. He and his wife enjoy traveling and camping.

Susan Wilson-Golab joined Oakland Schools in 2010 following 22 years of in the field 6-12 experience across two different states and rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Her research and practice focus heavily on the evolving definition of literacy, developmental learning progressions, and formative assessment. At the district level, Susan has served as classroom teacher, Literacy Specialist, and ELA Curriculum Coordinator. These experiences and study helped Susan in her role as Project Leader for developing a

Susan Wilson-Golab joined Oakland Schools in 2010 following 22 years of in the field 6-12 experience across two different states and rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Her research and practice focus heavily on the evolving definition of literacy, developmental learning progressions, and formative assessment. At the district level, Susan has served as classroom teacher, Literacy Specialist, and ELA Curriculum Coordinator. These experiences and study helped Susan in her role as Project Leader for developing a

We educators love our strategies, routines, and protocols though, especially with respect to reading. Indeed, much of the professional learning that I do with teachers involves, to varying degrees, strategies and routines. So my purpose here is not to say that protocols or strategies are inherently problematic, but rather I want to argue that we run the risk of minimizing the value of strategies if we use them in isolation, overuse them, use them when they don’t really fit, or use them without processing or connecting them to larger themes/concepts.

We educators love our strategies, routines, and protocols though, especially with respect to reading. Indeed, much of the professional learning that I do with teachers involves, to varying degrees, strategies and routines. So my purpose here is not to say that protocols or strategies are inherently problematic, but rather I want to argue that we run the risk of minimizing the value of strategies if we use them in isolation, overuse them, use them when they don’t really fit, or use them without processing or connecting them to larger themes/concepts.

Darin Stockdill is the Content Area Literacy Consultant at Oakland Schools. He joined the Learning Services team here in 2011 after completing his doctorate in the area of Literacy, Language, and Culture at the University of Michigan’s School of Education. At Michigan, he taught content area literacy methods courses to pre-service teachers (and was named a School of Education Outstanding Instructor in 2010) and researched adolescent literacy, with a focus on the connections (or lack thereof at times) between youths’ academic and non-academic literacy practices. Before this stint in academia, Darin was a classroom Social Studies and English teacher in Detroit for 10 years, working with both middle and high school students, and he also took on curriculum leadership roles in his school. Before teaching at the secondary level, he worked as a substance abuse and violence prevention specialist with youth in Detroit, and also taught literacy and ESL to adults in Chicago.

Darin Stockdill is the Content Area Literacy Consultant at Oakland Schools. He joined the Learning Services team here in 2011 after completing his doctorate in the area of Literacy, Language, and Culture at the University of Michigan’s School of Education. At Michigan, he taught content area literacy methods courses to pre-service teachers (and was named a School of Education Outstanding Instructor in 2010) and researched adolescent literacy, with a focus on the connections (or lack thereof at times) between youths’ academic and non-academic literacy practices. Before this stint in academia, Darin was a classroom Social Studies and English teacher in Detroit for 10 years, working with both middle and high school students, and he also took on curriculum leadership roles in his school. Before teaching at the secondary level, he worked as a substance abuse and violence prevention specialist with youth in Detroit, and also taught literacy and ESL to adults in Chicago. This American Life

This American Life When you use podcasts in this way in your classroom, students identify and analyze the implicit and explicit arguments being made in each “act” of a TAL podcast or other podcast, comparing the arguments within an episode. They can then respond with their own written or recorded narrative argument about the topic. This American Life episodes provide listeners with a series of narrative arguments around a single theme.

When you use podcasts in this way in your classroom, students identify and analyze the implicit and explicit arguments being made in each “act” of a TAL podcast or other podcast, comparing the arguments within an episode. They can then respond with their own written or recorded narrative argument about the topic. This American Life episodes provide listeners with a series of narrative arguments around a single theme. Multi-draft Listening

Multi-draft Listening Delia DeCourcy joined Oakland Schools in 2013 after a stint as an independent education consultant in North Carolina where her focus was on ed tech integration and literacy instruction. During that time, she was also a lead writer for the

Delia DeCourcy joined Oakland Schools in 2013 after a stint as an independent education consultant in North Carolina where her focus was on ed tech integration and literacy instruction. During that time, she was also a lead writer for the  During the twelve hour drive from Michigan to North Carolina and back over the holidays, I listened to a lot of podcasts. I admit it: I’m a podcast addict. Any time I have to drive for an hour or longer, I listen to a podcast–

During the twelve hour drive from Michigan to North Carolina and back over the holidays, I listened to a lot of podcasts. I admit it: I’m a podcast addict. Any time I have to drive for an hour or longer, I listen to a podcast– I remember talking to a colleague a few years ago who proclaimed that podcasting was not new media. She said it was just recorded radio and that podcasting was over. But podcasting is so not over and it’s a lot more than recorded radio. Sometimes podcasts never appear first on the radio at all. So why is this an important and popular media form?

I remember talking to a colleague a few years ago who proclaimed that podcasting was not new media. She said it was just recorded radio and that podcasting was over. But podcasting is so not over and it’s a lot more than recorded radio. Sometimes podcasts never appear first on the radio at all. So why is this an important and popular media form? In October, I was over the moon when

In October, I was over the moon when  It’s great storytelling and relevant to your students. The cast of characters is almost entirely high school students (or they were at the time of the murder) living through the things your students experience–juggling school and extracurriculars, navigating cultural differences between home life and school life, experiencing young love, making their way through the simmering stew of high school social life. This will seriously engage your students.

It’s great storytelling and relevant to your students. The cast of characters is almost entirely high school students (or they were at the time of the murder) living through the things your students experience–juggling school and extracurriculars, navigating cultural differences between home life and school life, experiencing young love, making their way through the simmering stew of high school social life. This will seriously engage your students. Engagement–what does it mean? How do we foster engagement in our classrooms? Like Marcia, I see learner identity as a key part of engaging learners. The idea of mindset playing a role in how a learner engages is well

Engagement–what does it mean? How do we foster engagement in our classrooms? Like Marcia, I see learner identity as a key part of engaging learners. The idea of mindset playing a role in how a learner engages is well  Not long ago, I came across Staci Hurst’s

Not long ago, I came across Staci Hurst’s

Susan Wilson-Golab joined Oakland Schools in 2010 following 22 years of in the field 6-12 experience across two different states and rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Her research and practice focus heavily on the evolving definition of literacy, developmental learning progressions, and formative assessment. At the district level, Susan has served as classroom teacher, Literacy Specialist, and ELA Curriculum Coordinator. These experiences and study helped Susan in her role as Project Leader for developing a

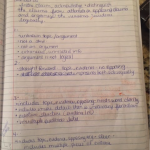

Susan Wilson-Golab joined Oakland Schools in 2010 following 22 years of in the field 6-12 experience across two different states and rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Her research and practice focus heavily on the evolving definition of literacy, developmental learning progressions, and formative assessment. At the district level, Susan has served as classroom teacher, Literacy Specialist, and ELA Curriculum Coordinator. These experiences and study helped Susan in her role as Project Leader for developing a  Current research surrounding literacy for students with significant disabilities has demonstrated that, with appropriate support and instruction, all students can be readers and writers. Traditionally, the approach has been a readiness model stating that literacy should be learned in a pre-determined, sequential manner that requires certain skills to be in place before the student can advance to the next level. The rigidity of this model has created barriers that many of our students can not overcome. The current view on literacy learning, however, focuses on enhancing communication and language opportunities to help students make connections and learn to use print in a meaningful way.

Current research surrounding literacy for students with significant disabilities has demonstrated that, with appropriate support and instruction, all students can be readers and writers. Traditionally, the approach has been a readiness model stating that literacy should be learned in a pre-determined, sequential manner that requires certain skills to be in place before the student can advance to the next level. The rigidity of this model has created barriers that many of our students can not overcome. The current view on literacy learning, however, focuses on enhancing communication and language opportunities to help students make connections and learn to use print in a meaningful way.

In July, I was selected to serve on a jury for an armed robbery trial at the Oakland County Courthouse. I’d never watched a real trial, only seen clips on CNN from particularly salacious, high-profile cases–Jodi Arias and Casey Anthony most recently. The armed robbery case wasn’t salacious, just kind of strange and full of inconsistencies. But just like on t.v., the stakes in the courtroom were high. And even more compelling were the elements of argument present throughout the trial–the defense and the prosecution battling it out over their claims, the witnesses presenting their versions of the story, which the lawyers shaped into evidence with their lines of questioning and opening and closing statements. Over those two and a half days, argument came to life for me in a way that it never had when I taught academic argument in middle school and college classrooms.

In July, I was selected to serve on a jury for an armed robbery trial at the Oakland County Courthouse. I’d never watched a real trial, only seen clips on CNN from particularly salacious, high-profile cases–Jodi Arias and Casey Anthony most recently. The armed robbery case wasn’t salacious, just kind of strange and full of inconsistencies. But just like on t.v., the stakes in the courtroom were high. And even more compelling were the elements of argument present throughout the trial–the defense and the prosecution battling it out over their claims, the witnesses presenting their versions of the story, which the lawyers shaped into evidence with their lines of questioning and opening and closing statements. Over those two and a half days, argument came to life for me in a way that it never had when I taught academic argument in middle school and college classrooms. The trial began with opening statements–the lawyers submitting claims of guilt and innocence to us with an overview of the evidence, angled differently by the prosecution and the defense. Our attention was grabbed; we were enticed first by one side, then the other. It felt a lot like the opening paragraphs of a good essay.

The trial began with opening statements–the lawyers submitting claims of guilt and innocence to us with an overview of the evidence, angled differently by the prosecution and the defense. Our attention was grabbed; we were enticed first by one side, then the other. It felt a lot like the opening paragraphs of a good essay. A few cops testified, then a friend of the supposed victim, and then the victim himself. No one had the same story. Few elements of the witnesses’ narratives even overlapped–there was a knife involved, and it was a bitter cold day. That was it. But the prosecutor and the defense attorneys’ lines of questioning were both artful — they constructed arguments with their questions.

A few cops testified, then a friend of the supposed victim, and then the victim himself. No one had the same story. Few elements of the witnesses’ narratives even overlapped–there was a knife involved, and it was a bitter cold day. That was it. But the prosecutor and the defense attorneys’ lines of questioning were both artful — they constructed arguments with their questions.