A few months ago, after soliciting ideas on social media, I selected The Junkard Wonders, by Michigan author/illustrator Patricia Polacco, as the Official Book of the Michigan Teacher of the Year 2016. The story compels readers to realize that no matter their ability, they are geniuses.

A few months ago, after soliciting ideas on social media, I selected The Junkard Wonders, by Michigan author/illustrator Patricia Polacco, as the Official Book of the Michigan Teacher of the Year 2016. The story compels readers to realize that no matter their ability, they are geniuses.

The message of The Junkyard Wonders is that we ought to seek out our genius, nurture it through hard work, and use our genius to contribute to the betterment of others and the world. We all belong, and we all have something to contribute to our communities, the book suggests.

This is a message that everyone needs to hear constantly. But no group needs to hear this idea more than our children—especially in the form of stories, read out loud.

As humans, our brains are hardwired for stories. We tune in naturally to the familiar architecture of a story arc, with its problems, solutions, characters, and settings. Joseph Campbell writes about the Hero’s Journey as a global story archetype, one that is common to all cultures around the globe. Our stories have always helped us not only to communicate, but to make sense of our world and realize our place in it. By reading aloud, we share these stories, and in doing so we create community.

People have also known for years that stories develop children’s vocabulary, improve their ability to learn to read, and—perhaps most important—foster a lifelong love of books and reading.

Associating Reading with Pleasure

The ability to develop a passionate reading life is crucial, according to Jim Trelease, author of the best-selling The Read-Aloud Handbook. “Every time we read to a child, we’re sending a ‘pleasure’ message to the child’s brain,” he writes in the Handbook. “You could even call it a commercial, conditioning the child to associate books and print with pleasure.”

The ability to develop a passionate reading life is crucial, according to Jim Trelease, author of the best-selling The Read-Aloud Handbook. “Every time we read to a child, we’re sending a ‘pleasure’ message to the child’s brain,” he writes in the Handbook. “You could even call it a commercial, conditioning the child to associate books and print with pleasure.”

This reading “commercial” is critical when competition for a child’s attention is so fierce. Between television, movies, the Internet, video games, and myriad after-school activities, the pleasures of sitting down with a book are often overlooked. In addition, negative experiences with reading—whether frustrations in learning to read or tedious “drill and kill” school assignments—can further turn children off from reading.

A child who does not have a healthy reading habit may suffer long-term consequences. As Trelease succinctly puts it, “Students who read the most, read the best, achieve the most, and stay in school the longest. Conversely, those who don’t read much, cannot get better at it.”

This is a relatively simple idea, and comes down to the importance of building a habit. Additionally, reading aloud is, according to the landmark 1985 report Becoming a Nation of Readers, “the single most important activity for building the knowledge required for eventual success in reading.”

Excitement in the Classroom

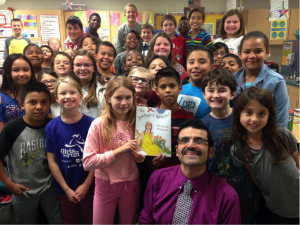

Auburn Elementary students after a read-aloud of The Junkyard Wonders

Recently, I read The Junkyard Wonders aloud to 5th graders at Deerfield and Auburn Elementary Schools, in the Avondale School District. The kids were enthralled with the story and connected easily with Polacco’s message of optimism, hope, and perseverance against all odds.

The next day, in an unrelated visit to Auburn, I stopped in the same classroom. What was most remarkable was that as soon as I entered, I was swarmed with kids who were thrusting their books in my face.

“Mr. Joe, have you read The Crossover?” came an inquiry from an eager 5th grade boy.

“I’m reading El Deafo. Have you read this book?” spat another.

“Look what I’m reading: Wonder. I love this book. Have you read it?” another asked.

I was flabbergasted that a read-aloud from the day before, to complete strangers, had created this instant reader-to-reader bond. I was reminded of out-loud reading’s intense power to stimulate a desire in the listener to grab a book and read more.

I felt part of a community of readers who talk about the stories they’ve read, try to make sense of them, and connect them to their own lives. Kids were so hungry to share their books with me. And they were hungry to communicate their excitement about stories—and to urge me to read, read, READ!

Rick Joseph is a National Board Certified Teacher and has taught 5/6 grade at Covington School in the Birmingham Public School district since 2003. Prior, he served as a bilingual educator and trainer for nine years in the Chicago Public Schools. Rick is thrilled to serve as the 2016 Michigan Teacher of the Year. Through Superhero Training Academy, Rick’s students have created a superhero identity to uplift the communities where they learn and live.

Rick Joseph is a National Board Certified Teacher and has taught 5/6 grade at Covington School in the Birmingham Public School district since 2003. Prior, he served as a bilingual educator and trainer for nine years in the Chicago Public Schools. Rick is thrilled to serve as the 2016 Michigan Teacher of the Year. Through Superhero Training Academy, Rick’s students have created a superhero identity to uplift the communities where they learn and live.

As a teacher who works with struggling readers, my favorite time of year is the end of the semester. It’s then that I assess students’ progress. When I give them their results, some can’t believe it. Some want to call their parents to share the good news. And some even cry. They all beam with pride.

As a teacher who works with struggling readers, my favorite time of year is the end of the semester. It’s then that I assess students’ progress. When I give them their results, some can’t believe it. Some want to call their parents to share the good news. And some even cry. They all beam with pride.

A real conversation, repeated yearly:

A real conversation, repeated yearly: It was inspiring and tragic to watch him try to tackle a book that matched his interests, but which was simply beating him down in terms of comprehension. I wasn’t about to tell him to quit; he’d come too far for me to do that to him.

It was inspiring and tragic to watch him try to tackle a book that matched his interests, but which was simply beating him down in terms of comprehension. I wasn’t about to tell him to quit; he’d come too far for me to do that to him.