Pulling in on the winding gravel road of Indian Trails Camp, I  took a deep breath. I was excited to arrive after the two hour commute on a sunny Sunday morning. To say I wasn’t nervous would be a lie. I was about to embark on what I had heard was an incredible, yet challenging week of intense learning. I, along with eight Oakland County teachers and two of my Oakland Schools colleagues, would spend the next seven days together attending a Level II course in Literacy for Students with Significant Disabilities at Camp ALEC. The course, taught by Drs. Koppenhaver and Erickson, exposes participants to over 60 hours of classroom learning, including providing literacy instruction for campers with significant disabilities. Little did I know that early Sunday morning that the experience would teach me so much more.

took a deep breath. I was excited to arrive after the two hour commute on a sunny Sunday morning. To say I wasn’t nervous would be a lie. I was about to embark on what I had heard was an incredible, yet challenging week of intense learning. I, along with eight Oakland County teachers and two of my Oakland Schools colleagues, would spend the next seven days together attending a Level II course in Literacy for Students with Significant Disabilities at Camp ALEC. The course, taught by Drs. Koppenhaver and Erickson, exposes participants to over 60 hours of classroom learning, including providing literacy instruction for campers with significant disabilities. Little did I know that early Sunday morning that the experience would teach me so much more.

I learned before the campers arrived that the two girls I would instruct during this week were 12 years old. I first met Maggie when she arrived with her Mom and younger brother. As her Mom navigated her wheel chair, my first glimpse of Maggie, appearing so helpless and limp in the chair, brought tears to my eyes. You see, my own daughters are 12 and 13 years old. Funny how we can so easily make assumptions about someone based on a first impression. Here I was, a Special Education teacher, feeling so blessed for my own daughters, when Maggie taught me one of the biggest lessons I would learn all week: She rolled her eyes at her Mom, who had just apparently annoyed her with a comment, just like my own daughters do. Maggie could not talk, but boy could she communicate! I knew I was in for an amazing week.

The training I have received over the years reflects a belief that teaching literacy to students with significant disabilities does not require “prerequisites” or “readiness” or that literacy can only be learned by “higher functioning” students. We all learn to read and write in basically the same ways, but literacy instruction for students with significant disabilities requires a more deliberate and concentrated effort to ensure the student has access to communication and learning. It requires a commitment to lots of time dedicated to comprehensive literacy instruction. If a student is not learning, we as educators need to figure out what is not working. It is our responsibility to provide meaningful instruction that offers repetition with lots of variety to engage and help these students generalize their learning in multiple environments. This and other principles of good ELA instruction are described in a DLM (Dynamic Learning Maps) module.

So knowing what good instruction is and actually teaching are two very different things. My partner for the week, Darlene, and I spent our planning time designing lessons to reflect what we knew to be good instruction. Maggie and Josie spent two hours with us in the morning and afternoon. Our job was to provide their parents by week’s end a summary of activities we tried and ideas for helping their daughter improve in the area of literacy. We completed some assessments to help guide our instruction and quickly learned that things don’t always go as planned. We needed to give ourselves permission to get to know the girls and understand their interests.

So knowing what good instruction is and actually teaching are two very different things. My partner for the week, Darlene, and I spent our planning time designing lessons to reflect what we knew to be good instruction. Maggie and Josie spent two hours with us in the morning and afternoon. Our job was to provide their parents by week’s end a summary of activities we tried and ideas for helping their daughter improve in the area of literacy. We completed some assessments to help guide our instruction and quickly learned that things don’t always go as planned. We needed to give ourselves permission to get to know the girls and understand their interests.

Once we anchored our lessons based on the girls’ experiences, they started to make connections. Josie, for example, loved to play Tag with anyone who would run with her. We started taking pictures of her and others playing, printed them and shared the collection with Josie. I glued the pictures onto paper, showed Josie and waited for her response. She quickly started signing and verbalizing her descriptions of the pictures while laughing and smiling. It was clearly a motivating activity for Josie. I then handed her a pen and asked her to tell me  about her pictures. Josie’s smile left her face and she signed “nervous”. She was not comfortable with this request, but with encouragement and permission to write in short segments throughout the week, she created a book about playing Tag. When her mom arrived Saturday, Josie read her the Tag book she created. This process required creativity to engage Josie and patience on my part to allow her the time she needed to express herself.

about her pictures. Josie’s smile left her face and she signed “nervous”. She was not comfortable with this request, but with encouragement and permission to write in short segments throughout the week, she created a book about playing Tag. When her mom arrived Saturday, Josie read her the Tag book she created. This process required creativity to engage Josie and patience on my part to allow her the time she needed to express herself.

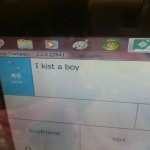

Another opportunity for making connections to the girls’ experiences came about the last day of camp. Maggie relies on an alternate communication device; she is unable to speak and has physical limitations that make using her hands for signing impossible. Despite these limitations, Maggie had a very typical “goal” for camp: she wanted to kiss a boy! She achieved her goal (Luke gave her a kiss on the cheek) and was so excited. She even texted her mom, letter by letter, using a head mouse connected to her device mounted on her wheel chair.

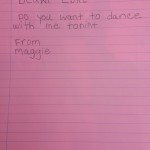

There was a dance Friday night and one of the counselors suggested that maybe she and Luke could dance. Maggie smiled and typed out “Write a note to ask him.” Unfortunately, Maggie was in a lot of pain that day. Her chair was bothering her and she kept saying that her back hurt. Karen Erickson came by and asked Maggie if she would like to lay down. I was disappointed, thinking Maggie would have to go back to her cabin, but there was a bean bag in the room, and Maggie’s counselor transferred her. In a more comfortable position, but without her device, Karen guided me through an alternate way of helping Maggie write her note. With a pad of paper on my lap, I went through the alphabet, letter by letter, until Maggie raised her eyes for “yes”. I wrote down each letter until she completed what she wanted to write:

Maggie gave her note to Luke at lunch, and the two shared a sweet dance. If Maggie had not been given the opportunity to switch positions, she likely would not have written her note. We as teachers need to embrace teachable moments even when obstacles arise. This method was shared with Maggie’s Mom, who immediately saw the potential for using this to communicate with Maggie during car rides. Instead of crying to let her Mom knows she needs something, she now has access to the alphabet when hooking up her device is not convenient.

Based on observations and assessments given to the girls, a recommendation for reading easy books would help with print processing and language difficulties. One resource shared with both girls was Tarheel Reader. This free site houses thousands of easy-to-read and accessible books on a wide range of topics. Each book can be speech enabled and accessed using multiple interfaces, including touch screens and the IntelliKeys with custom overlays. Both Maggie and Josie loved going on the site and searching out books. Maggie even bookmarked the site as a favorite. She now has independent access to thousands of books.

Saturday morning, the teachers from Oakland County and I shared our excitement for the upcoming school year. They agreed that this camp experience was an incredible and yes, challenging experience. They are now teacher leaders and will enter the school year with a deeper, richer understanding of teaching literacy to students with significant disabilities.

Oakland Schools will offer one day sessions on Emergent and Conventional Literacy Instruction in March, 2016. Please visit the Special Education Professional Learning section of our website for more details.

A local newspaper highlighted Camp ALEC during the week. Click here to see the video.

Colleen Meszler joined Oakland Schools in 1994 after earning her special education teaching degree from Eastern Michigan University. She holds a Master’s Degree in Special Education with endorsements in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Emotional Impairment and is approved as an ASD Teacher Consultant. Her passion is supporting the unique learning needs of students with Autism. Her work has changed over the years as Oakland Schools has responded to the changing needs of the districts in the county. She began as a teacher in the Oakland Schools Autism Program educating middle school and post-high students. She then provided ASD Teacher Consultant services to the districts of Oakland County, again focusing on the needs of students with ASD.

Colleen Meszler joined Oakland Schools in 1994 after earning her special education teaching degree from Eastern Michigan University. She holds a Master’s Degree in Special Education with endorsements in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Emotional Impairment and is approved as an ASD Teacher Consultant. Her passion is supporting the unique learning needs of students with Autism. Her work has changed over the years as Oakland Schools has responded to the changing needs of the districts in the county. She began as a teacher in the Oakland Schools Autism Program educating middle school and post-high students. She then provided ASD Teacher Consultant services to the districts of Oakland County, again focusing on the needs of students with ASD.

In her current role as a Special Education Consultant in the Professional Learning Unit of the Department of Special Education, Colleen supports public school special educators as they close the achievement gap between students with and without IEPs. Specifically, she facilitates the professional learning of special educators in the provision of emergent and conventional literacy instruction to students with moderate to significant cognitive disabilities. The emphasis is on instructional practices for pre-K through post-high students who are educated to alternate achievement standards and assessed through the alternate state assessment.

Colleen stays busy on the home front as well, attending soccer and volleyball games, boating and snowmobiling with her husband and two daughters.

“Every child is born a genius, but is swiftly degeniused by unwitting humans and/or physically unfavorable environmental factors.”

“Every child is born a genius, but is swiftly degeniused by unwitting humans and/or physically unfavorable environmental factors.” As a career reading and writing teacher, I was utterly impressed by the students in a writing workshop who were taking turns sharing personal narrative pieces in their weekly author’s chair. These students were extraordinary in their passionate writing and dynamic storytelling. The fact that they all had very significant learning differences made me realize that with effective, dedicated instruction, their voices can be heard as easily as those of students in a regular education setting.

As a career reading and writing teacher, I was utterly impressed by the students in a writing workshop who were taking turns sharing personal narrative pieces in their weekly author’s chair. These students were extraordinary in their passionate writing and dynamic storytelling. The fact that they all had very significant learning differences made me realize that with effective, dedicated instruction, their voices can be heard as easily as those of students in a regular education setting. Rick Joseph is a National Board Certified Teacher and has taught 5/6 grade at Covington School in the Birmingham Public School district since 2003. Prior, he served as a bilingual educator and trainer for nine years in the Chicago Public Schools. Rick is thrilled to serve as the 2016 Michigan Teacher of the Year. Through Superhero Training Academy, Rick’s students have created a superhero identity to uplift the communities where they learn and live.

Rick Joseph is a National Board Certified Teacher and has taught 5/6 grade at Covington School in the Birmingham Public School district since 2003. Prior, he served as a bilingual educator and trainer for nine years in the Chicago Public Schools. Rick is thrilled to serve as the 2016 Michigan Teacher of the Year. Through Superhero Training Academy, Rick’s students have created a superhero identity to uplift the communities where they learn and live.

took a deep breath. I was excited to arrive after the two hour commute on a sunny Sunday morning. To say I wasn’t nervous would be a lie. I was about to embark on what I had heard was an incredible, yet challenging week of intense learning. I, along with eight Oakland County teachers and two of my Oakland Schools colleagues, would spend the next seven days together attending a Level II course in Literacy for Students with Significant Disabilities at

took a deep breath. I was excited to arrive after the two hour commute on a sunny Sunday morning. To say I wasn’t nervous would be a lie. I was about to embark on what I had heard was an incredible, yet challenging week of intense learning. I, along with eight Oakland County teachers and two of my Oakland Schools colleagues, would spend the next seven days together attending a Level II course in Literacy for Students with Significant Disabilities at