Several years ago, I developed an inquiry question that asked if students use the language of workshop. Because I consistently use the “ELA Speak” of mentor texts, seed ideas, and generating strategies, I questioned, do students know these terms and use them to forge work?

Several years ago, I developed an inquiry question that asked if students use the language of workshop. Because I consistently use the “ELA Speak” of mentor texts, seed ideas, and generating strategies, I questioned, do students know these terms and use them to forge work?

This work began with a checklist of workshop language that I wanted students to leave eighth grade knowing and using. I culled the list from the ELA Common Core State Standards, the MAISA Units of Study, and my lesson plans.

I decided I would look at summative writing work to evaluate students’ use of these skills. Additionally, I felt strongly about students having their voice heard, so final work was accompanied by a reflection which asked students to name skills they now had as writers, to give examples of these skills in their writing, and to set a goal for future use of these skills.

Originally, I modeled a reflection that focused on the end-product skills my writing showed, and student reflections did the same. In my example, I wrote a reflection on our opening unit about narrative poetry. In this reflection you can see how I named skills that are explicitly evident in the published final copy, such as craft skills (alliteration, repetition) and theme.

I shouldn’t have been surprised by this, but as I recorded language students named and used correctly or used and didn’t name, I realized that they were using the language of workshop, however, the tool I gave them to show this understanding didn’t allow everything to be shown. Namely, students didn’t name process skills or skills that students used to develop a final product, but I could see evidence of this work in my conference notes and in their drafts. In the next reflection, for the same unit a year later, you can see that I named generating and finding seeds as part of the journey to finding the topic I wrote about. Additionally, I explained several more skills that I used as a writer such as the overall structure and type of ending.

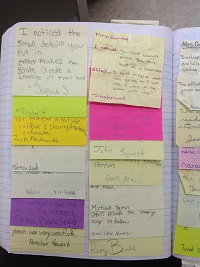

So, I made two changes. First, I more explicitly named the skills and associated lessons. I even hung these up in my classroom during the unit (pictured is literary essay unit).

Second, I created a model reflection that named process skills in addition to the end-product skills shown in my writing. I also exhibited this more thoroughly by writing in specific lines of my text that exhibit the traits I name in my reflection: Revised Reflection 2.

Now, student reflections named all of the skills learned and used. So, I know from reflections that students use the language of workshop in theory and in practice.

Reflections serve another purpose, though. As I grade the writing, according to a rubric which for me is a curricular model rubric assessing organization, content, and language use, I used student reflections as an accompaniment to reading the writing. For many language arts teachers, we take the student into account on these summative grades by considering, the growth that the student has achieved from conference suggestions, the specific use of skills from lessons, and the ability of the student.

As I read a student’s literary essay, I commented about the depth of commentary with the statement, “Commentary – how does this evidence relate to your claim/topic?” In my classroom, I work with students to understand that commentary re-explains evidence, tells why evidence is important, and relates evidence to claim, topic, other evidence. I muddled between the score of adequate and below. Deciding on adequate for the overall content of the paper, I read the student’s matching reflection. He stated in the future goals section, “I would take more time, and think deeper about what my claim should be. I think that I took the easy and the most obvious route. If I had taken more time, and thought deeper, I could have created a more sophisticated essay with better evidence and commentary.” This statement validated the “adequate” score I gave for the student’s essay content.

Overall, I use reflections to inform my teaching and to give students voice as I grade their papers. In the example, above, it was as if the student was sitting next to me as I graded the writing. Throughout the year, as students reflect on each unit of reading and writing, they can see their growth over time. As students are allowed to think about what they have actually learned through the course of a unit and show evidence of that learning, the writer improves more quickly over time because they can think deeply about their writing decisions and exhibit inquiries about their own work. These inquiries help to increase the amount of independence the writer possesses while writing because they can make choices about the writing they publish.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the MAISA units of study. She has studied, researched, and practiced reading and writing workshop through Oakland Schools, The Teacher’s College, and action research projects. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Education at Central Michigan University and a Master’s in Educational Administration at Michigan State University.

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts.

This tool is exclusively available for Google Education users and manages class lists and links to student’s Google Drive accounts. This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on.

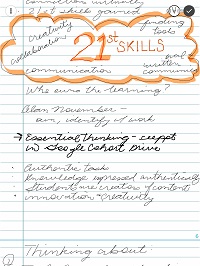

This platform houses online documents that can be created, shared, and collaborated on. This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

This program’s purpose is online organization and notebook creation. Penultimate is an Evernote sister app which syncs data but also allows handwritten notes.

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Next week, we’ll spend a day in class where they’ll look at their past essays and really read my comments (a girl can dream, right?). Then they’ll talk about those essays with each other and set some goals for this next piece. I’m hoping the goals will be more like “I will make sure my analysis in my body paragraphs directly relates to my thesis” and less like “I will get an A.” We’ll see. One way I hope to get at this is some reflective journaling throughout the process. We’ll set the goals at the beginning of the process, but then I’m going to ask the students to revisit those goals throughout the writing process. What have they done to achieve those goals? What struggles are they having? Hopefully, by asking them to articulate their progress, they’ll begin to realize that they are the ones in control of improving their writing.

Next week, we’ll spend a day in class where they’ll look at their past essays and really read my comments (a girl can dream, right?). Then they’ll talk about those essays with each other and set some goals for this next piece. I’m hoping the goals will be more like “I will make sure my analysis in my body paragraphs directly relates to my thesis” and less like “I will get an A.” We’ll see. One way I hope to get at this is some reflective journaling throughout the process. We’ll set the goals at the beginning of the process, but then I’m going to ask the students to revisit those goals throughout the writing process. What have they done to achieve those goals? What struggles are they having? Hopefully, by asking them to articulate their progress, they’ll begin to realize that they are the ones in control of improving their writing. Student-led modeling: I often write my own essay along with my students a la Penny Kittle’s

Student-led modeling: I often write my own essay along with my students a la Penny Kittle’s  Hattie Maguire is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her fourteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition, English 10, Debate, and Practical Public Speaking. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University.

Hattie Maguire is an English teacher and Content Area Leader at Novi High School. She is spending her fourteenth year in the classroom teaching AP English Language and Composition, English 10, Debate, and Practical Public Speaking. She is a National Board Certified Teacher who earned her BS in English and MA in Curriculum and Teaching from Michigan State University. We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students?

We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students? Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students?

Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students? Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the