Read The Tumblr Experiment, part 1: Introduction

The blogging universe is huge and can feel overwhelming, so my students’ first challenge was to carve out a bit of it for our own community. Our first assignment was to create blogs and find each other. Enter the hashtag. Students know how to use hashtags to organize their posts or tweets around topics, so I use them with Tumblr as well. Our first one is aplang15hello. Hashtags are a great way to tame the vastness of the blogosphere, but I need something that’s easy to identify and stands out. The first part identifies the class and the second part, after the 15, is the subject. This is our way to “find” each other. We search for the unique hashtag which leads us to each others’ blogs. Then it’s a simple click on the “Follow” button and, hello audience.

The blogging universe is huge and can feel overwhelming, so my students’ first challenge was to carve out a bit of it for our own community. Our first assignment was to create blogs and find each other. Enter the hashtag. Students know how to use hashtags to organize their posts or tweets around topics, so I use them with Tumblr as well. Our first one is aplang15hello. Hashtags are a great way to tame the vastness of the blogosphere, but I need something that’s easy to identify and stands out. The first part identifies the class and the second part, after the 15, is the subject. This is our way to “find” each other. We search for the unique hashtag which leads us to each others’ blogs. Then it’s a simple click on the “Follow” button and, hello audience.

This first project, High Art, grew out of my frustration with the kinds of essays I typically assigned. I asked students to evaluate and make a case for a novel that they liked to be placed in our curriculum. As a writing assignment it was ok (zzzz), but the products lacked passion and voice. Students didn’t really care about novels or my opinion of novels, so they didn’t really care about the writing. My problem was that I didn’t know what they were passionate about and didn’t have a good way to find out.

I also came up against the audience problem. Having their teacher as audience/evaluator/giver of points meant they wrote safe and “schooly”–their word–rather than honestly. I didn’t want safe writing. I wanted them to take chances, fail sometimes, learn and then come back again.

I also came up against the audience problem. Having their teacher as audience/evaluator/giver of points meant they wrote safe and “schooly”–their word–rather than honestly. I didn’t want safe writing. I wanted them to take chances, fail sometimes, learn and then come back again.

When I started to flirt with the idea of using Tumblr blogs in class, I lurked around in the space watching for and thinking about the kinds of writing I wanted my students to try, and I kept coming back to the idea of voice–authentic, honest and passionate. That voice, it seemed to me, was often found around subjects that the the writers were passionate about–music, movies, television shows, pop culture–sure, but still culture. And tucked in there among the pop culture were a lot of other things too–art things like body art and anime and illustrations. Art? Could I ask them to write about art? Why not?

It’s subjective. No one I was reading seemed able to clearly define it, but most of the writers seemed passionate that what they liked was most definitely Art. We were writing about novels, and it’s not much of a pivot from writing an argument about books to writing an argument about art. So, art it was. We looked at some examples of “high” and “low” art and culture, talked about criteria and evaluation and then jumped in. For their first assignment, I ask for students’ definition of art. I know. That’s daunting and very subjective, but for those very reasons it seemed like a logical starting point. It’s a challenging topic, but you can’t really get it “wrong.” And it’s a good way for students to introduce their “honest yet academic” selves. (More on this self idea in an upcoming post on Speaker–Who are you? Who do do want to be?)

This image shows some of our initial forays on to the Tumblr microblogging platform. Tumblr microblogs typically offer shorter content than blogs, another aspect that drew me to it. It’s less daunting than the essay-like blog but more demanding that something like Twitter.

This image shows some of our initial forays on to the Tumblr microblogging platform. Tumblr microblogs typically offer shorter content than blogs, another aspect that drew me to it. It’s less daunting than the essay-like blog but more demanding that something like Twitter.

Students did pretty well once we got past the challenges. I always have to remind myself that just because my students are digital natives doesn’t mean that they are all good at technology. I had to work through issues of sign ups, access (my district, like many others, tends to be squeamish when it comes to anything that smells even remotely like social networking sites, so firewalls and filters are a constant challenge), how to “find” each other and the blogs we want to follow, commenting, and reblogging. There’s always something. My response is to remain calm and find a workaround. Eventually it all worked out, and we managed to create some content. It was mostly in the form of reblogging–repeating something interesting that you found on someone else’s blog–and then adding to the discussion with some original writing.

The students would mine the blogs they followed for content that they could write about and reblog under a our class hashtag–things they were genuinely interested in. Using the class hashtag meant it would show up in the feeds of their classmates. If they picked the right content and presented it well, they’d get a response for another classmate. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t.

It’s here where our discussion about audience starts to bear out. What kind of writing attracts and holds our attention? Tumblr is an image rich environment with most users simply scrolling through until something catches their attention. The question for writers becomes: how do we compete for that attention?

It’s here where our discussion about audience starts to bear out. What kind of writing attracts and holds our attention? Tumblr is an image rich environment with most users simply scrolling through until something catches their attention. The question for writers becomes: how do we compete for that attention?

The images blur by, but my students agree that it’s often the writing that “sticks.” So how do we get “sticky?” I assign (compel?) my students to, in addition to writing their own content, reblog and comment on a certain number of their classmates’ posts. Making this an assignment is cheating because we’re not really creating any original content–more like offering opinions and observations–but it’s a good way to join the Tumblr discussion. It does require student bloggers to look at each others’ writing, but the challenge to attract attention, create a buzz, get sticky, is still with the writer. How do writers attract attention? What kinds of writing stick to a reader’s attention? Usually I’d approach these questions by assigning an essay and we’d start to close read and analyze it. Now the students’ work is where we start. I look through their work for what I call “good exchanges.”

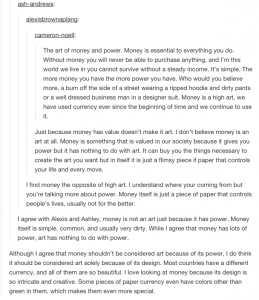

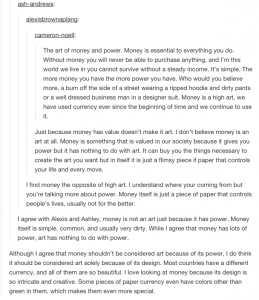

A “Good Exchange” showing a couple of students engaged in exchanging views over an idea about art.

The image at the right shows what a good exchange on Tumblr might look like. The original writer reblogged and wrote about something in a way that provoked his audience–his classmates–to “like,” “reblog,” and then respond. I’ll project this on the board and then we’ll talk about how and why the writing works. We give feedback and talk about the choices the writers made and how they worked. For me, this is a goldmine of teachable moments. I can talk directly to the intended audience because they’re sitting in the same room next to the writer who I can ask to talk about the choices she made and what her purpose was. We still close read professional writers, still look to the masters for guidance and models, but now I have another set of models, another set of writers. These writers are us. We’re not simply studying writing; we are writing, and about things we’re passionate about, just like Swift and Orwell and Wolff–all of whomI think would be terrific bloggers.

The Tumblr experiment is underway and most of the tech issues are solved. So where do we go next? It’s engaging and fun. My students like the attention, and I like having all of this material to use in my teaching but, they still ask me what it’s worth.

“Hey, um, Mr. Kreinbring-kreinbring65- or whatever we’re supposed to call you, points, how many are we getting for all this writing? Sure, it’s more engaging and all that but, you know, what’s my grade?”

They still ask that. They still have a hard time seeing past grades and points as the reason to do all of this writing. It’s not a question I like, but it is valid. How am I, their teacher, (and they still see me a that way, not as a fellow blogger) using all of this work to evaluate them? How am I rewarding good work and encouraging others to work harder at this?

I honestly do not know…yet.

I do know that my goal is to get students thinking of themselves as writers, as part of a community that skillfully uses words and images to explore ideas that matter to them, but they’re worried about their grades. Frustrating as it is I understand this, but we are moving in the right direction because they’re primarily looking more at one another as the audience and second at me as the “evaluator.” I see them engaging with each other but with an awareness of me. I don’t know if I’ll be able to completely move them from thinking of themselves as members of a class with the goal of getting a good grade to members of a community of writers with the goal of becoming better writers but this experiment; this feels like a first step in right direction.

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a statewide research project through the Michigan Teachers as Researchers Collaborative partnered with the MSU Writing in Digital Environments Program, which concentrates on improving student writing and peer feedback. Rick has presented at the National Advanced Placement Convention and the National Council of Teachers of English Conference. He is in his twenty-third year of teaching and makes his home in Huntington Woods.

The blogging universe is huge and can feel overwhelming, so my students’ first challenge was to carve out a bit of it for our own community. Our first assignment was to create blogs and find each other. Enter the hashtag. Students know how to use hashtags to organize their posts or tweets around topics, so I use them with Tumblr as well. Our first one is aplang15hello. Hashtags are a great way to tame the vastness of the blogosphere, but I need something that’s easy to identify and stands out. The first part identifies the class and the second part, after the 15, is the subject. This is our way to “find” each other. We search for the unique hashtag which leads us to each others’ blogs. Then it’s a simple click on the “Follow” button and, hello audience.

The blogging universe is huge and can feel overwhelming, so my students’ first challenge was to carve out a bit of it for our own community. Our first assignment was to create blogs and find each other. Enter the hashtag. Students know how to use hashtags to organize their posts or tweets around topics, so I use them with Tumblr as well. Our first one is aplang15hello. Hashtags are a great way to tame the vastness of the blogosphere, but I need something that’s easy to identify and stands out. The first part identifies the class and the second part, after the 15, is the subject. This is our way to “find” each other. We search for the unique hashtag which leads us to each others’ blogs. Then it’s a simple click on the “Follow” button and, hello audience. I also came up against the audience problem. Having their teacher as audience/evaluator/giver of points meant they wrote safe and “schooly”–their word–rather than honestly. I didn’t want safe writing. I wanted them to take chances, fail sometimes, learn and then come back again.

I also came up against the audience problem. Having their teacher as audience/evaluator/giver of points meant they wrote safe and “schooly”–their word–rather than honestly. I didn’t want safe writing. I wanted them to take chances, fail sometimes, learn and then come back again. This image shows some of our initial forays on to the Tumblr microblogging platform. Tumblr microblogs typically offer shorter content than blogs, another aspect that drew me to it. It’s less daunting than the essay-like blog but more demanding that something like Twitter.

This image shows some of our initial forays on to the Tumblr microblogging platform. Tumblr microblogs typically offer shorter content than blogs, another aspect that drew me to it. It’s less daunting than the essay-like blog but more demanding that something like Twitter. It’s here where our discussion about audience starts to bear out. What kind of writing attracts and holds our attention? Tumblr is an image rich environment with most users simply scrolling through until something catches their attention. The question for writers becomes: how do we compete for that attention?

It’s here where our discussion about audience starts to bear out. What kind of writing attracts and holds our attention? Tumblr is an image rich environment with most users simply scrolling through until something catches their attention. The question for writers becomes: how do we compete for that attention?

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a

Rick Kreinbring teaches English at Avondale High School in Auburn Hills, Michigan. His current assignments include teaching AP Language and Composition and AP Literature and Composition. He is a member of a  28 weeks. When I hear this I think of being just more than halfway through a pregnancy. While I am not having a baby, I am witnessing the growth and development of my classroom of writers. According to my teacher blog, I have assigned 19 posts, not counting the daily expectation for this month. We have been blogging weekly since the school year began. I started this process mainly as preparation for the

28 weeks. When I hear this I think of being just more than halfway through a pregnancy. While I am not having a baby, I am witnessing the growth and development of my classroom of writers. According to my teacher blog, I have assigned 19 posts, not counting the daily expectation for this month. We have been blogging weekly since the school year began. I started this process mainly as preparation for the  Does this mean that all of my students are suddenly writing beautiful blog posts, with wonderful spelling and grammar? Nope. In fact, there are some downright cringe-worthy pieces of writing on our class pages. But they are excited, they want to write, and they are paying more attention. When we give comments, I tell my students to tell the writer specifically what they have done well. My hope is that they will begin to transfer some of this attention to their own work. In small increments, I am seeing evidence of this. I only have to scroll back to September to see the growth right in front of me. I also set out Chromebooks at conferences so parents can peruse their child’s blog while they wait. This is very informative and often makes conversations easier.

Does this mean that all of my students are suddenly writing beautiful blog posts, with wonderful spelling and grammar? Nope. In fact, there are some downright cringe-worthy pieces of writing on our class pages. But they are excited, they want to write, and they are paying more attention. When we give comments, I tell my students to tell the writer specifically what they have done well. My hope is that they will begin to transfer some of this attention to their own work. In small increments, I am seeing evidence of this. I only have to scroll back to September to see the growth right in front of me. I also set out Chromebooks at conferences so parents can peruse their child’s blog while they wait. This is very informative and often makes conversations easier. Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.

Beth Rogers is a fifth grade teacher for Clarkston Community Schools, where she has been teaching full time since 2006. She is blessed to teach Language Arts and Social Studies for her class and her teaching partner’s class, while her partner teaches all of their math and science. This enables them to focus on their passions and do the best they can for kids. Beth was chosen as Teacher of the Year for 2013-2014 in her district. She earned a B.S. in Education at Kent State University and a Master’s in Educational Technology at Michigan State University.  The writer’s notebook is almost a sacred, mythical element of the writer’s workshop. It is where students’ writing lives take shape and are documented over the course of a year. In my classroom, the writer’s notebook held everything, and I mean EVERYTHING. Any paper I handed out was immediately taped or glued into the notebook, even if it had to be turned on its side or folded over two times. The writer’s notebook was our textbook. So when I heard each one of my students would be getting a Chromebook, I was excited about the possibilities and what that could mean for student writing. But what nagged at me was the loss of the traditional, tangible writer’s notebook.

The writer’s notebook is almost a sacred, mythical element of the writer’s workshop. It is where students’ writing lives take shape and are documented over the course of a year. In my classroom, the writer’s notebook held everything, and I mean EVERYTHING. Any paper I handed out was immediately taped or glued into the notebook, even if it had to be turned on its side or folded over two times. The writer’s notebook was our textbook. So when I heard each one of my students would be getting a Chromebook, I was excited about the possibilities and what that could mean for student writing. But what nagged at me was the loss of the traditional, tangible writer’s notebook. Instead of kids bringing their notebooks to one another and reluctantly allowing a partner to write on their prized draft, kids are sharing documents with one another and setting the editing level based on their comfort, with many choosing to only allow their partners to comment on a document. They no longer have to worry that someone is going to “mess up” their paper. They can simply focus on the comments, and especially relish hitting the “Resolve” button when they have revised something. I think it’s more than just reading the comments and making changes, though; kids are having conversations via their comments about writing as well as having conversations about their writing out loud. The conversations about writing are multilayered. If you’ve ever seen a teen text and talk to someone at the same time, you know that holding multiple conversations on various platforms is a way of life. And students also seem to be more responsive to my suggestions because my comments don’t physically change their writing; they are seen as just that: comments and suggestions.

Instead of kids bringing their notebooks to one another and reluctantly allowing a partner to write on their prized draft, kids are sharing documents with one another and setting the editing level based on their comfort, with many choosing to only allow their partners to comment on a document. They no longer have to worry that someone is going to “mess up” their paper. They can simply focus on the comments, and especially relish hitting the “Resolve” button when they have revised something. I think it’s more than just reading the comments and making changes, though; kids are having conversations via their comments about writing as well as having conversations about their writing out loud. The conversations about writing are multilayered. If you’ve ever seen a teen text and talk to someone at the same time, you know that holding multiple conversations on various platforms is a way of life. And students also seem to be more responsive to my suggestions because my comments don’t physically change their writing; they are seen as just that: comments and suggestions.  I had toyed with the idea of having students use a single, running Google Doc to keep a notebook, but that doesn’t work as easily as a traditional notebook does, especially when using Google Classroom, because some of the documents would be in Classroom and some would be in the running Google Doc. I thought toggling between the two would be difficult. Obviously, no single platform seems to be perfect (it’s unlikely that anything will ever meet every need/want). Despite the misgivings I may have, my students do not seem to be having the same internal struggles that I am having. Using their Chromebooks has quickly become second nature, with the biggest complaint being that the WiFi isn’t working quickly enough!

I had toyed with the idea of having students use a single, running Google Doc to keep a notebook, but that doesn’t work as easily as a traditional notebook does, especially when using Google Classroom, because some of the documents would be in Classroom and some would be in the running Google Doc. I thought toggling between the two would be difficult. Obviously, no single platform seems to be perfect (it’s unlikely that anything will ever meet every need/want). Despite the misgivings I may have, my students do not seem to be having the same internal struggles that I am having. Using their Chromebooks has quickly become second nature, with the biggest complaint being that the WiFi isn’t working quickly enough! ianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a

ianna Taylor is an ELA and Title 1 teacher at Orchard Lake Middle School in West Bloomfield. She is a member of the AVID Site Team and Continuous School Improvement Team at her school, among other things. She is also a  We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students?

We’ve reached the point in my 8th grade classroom where we’ve modeled, practiced, and established norms that we can use in our workshop classroom. Additionally, I have also conferenced with each student to give them a next step as they continue their reading and writing work. This, however, is not a blog post about effective conferencing, rather it’s about what I’ve learned from conferencing with a particular student. This experience leaves me wondering whether we, as teachers, always realize the effects we have on students? Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students?

Amidst these in-class conferences with Kyle, I met Kyle’s mom. She shared a story with me about a 3rd grade teacher who told Kyle that he was not a writer. While I’m not writing this post to place blame, I see that when Kyle sits down to write, he does so with doubt. This doubt may have come from the seed planted by that teacher, but it probably also came from many other writing experiences that perhaps didn’t go as Kyle had hoped. In the end, Kyle had a very successful first writing unit in my classroom, and I hope that he’ll continue to feel excited about writing as we get into argument and informative writing. But this whole episode left me wondering–what effects do we, as teachers, have on students? Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

Amy Gurney is an 8th grade Language Arts teacher for Bloomfield Hills School District. She was a facilitator for the release of the

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures.

This experience showed me and Doug that it is imperative for disciplines to collaborate. Neither of us could have gotten the quality of work the students produced had we done this separately. For the first time, students were seeing exactly how the skills they learn in their individual classes apply to all classes. They were developing skills–research skills, presentation skills– not just memorizing facts and figures. Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the

Lisa Kraiza teachers eighth grade English Language Arts at Oak Park Preparatory Academy. She is also a member of the Core Leadership Team of the  Several years ago, I went in search of an audience for my students, although at the time I didn’t know that was what I was up to. I’d seen enough student writing to know I wasn’t doing something right in my instruction. My students were smart, interesting and capable of all manner of argument, but their writing didn’t reflect that. However, they were willing to risk suspension by breaking through the district’s internet firewall to reach sites like Myspace and Facebook where they wrote (Wrote!) about things they cared about in ways that reflected their personalities. This was what I was looking for. So I started a website where my students and I could build on the conversations we were having in class, and they could write in the same way they wrote on social media sites. I envisioned a free flowing forum of ideas and enthusiasm, a place for authentic voices like I’d seen on Facebook and Myspace, like I’d heard in my classroom. Yeah, I was wrong.

Several years ago, I went in search of an audience for my students, although at the time I didn’t know that was what I was up to. I’d seen enough student writing to know I wasn’t doing something right in my instruction. My students were smart, interesting and capable of all manner of argument, but their writing didn’t reflect that. However, they were willing to risk suspension by breaking through the district’s internet firewall to reach sites like Myspace and Facebook where they wrote (Wrote!) about things they cared about in ways that reflected their personalities. This was what I was looking for. So I started a website where my students and I could build on the conversations we were having in class, and they could write in the same way they wrote on social media sites. I envisioned a free flowing forum of ideas and enthusiasm, a place for authentic voices like I’d seen on Facebook and Myspace, like I’d heard in my classroom. Yeah, I was wrong. This all happened at the turn of the century, but the idea of 21st century literacy wasn’t on my radar. I wasn’t thinking about how drastically teaching reading and writing was going to be impacted by the World Wide Web. I just wanted to be in on what was happening. Though my first failures did send me in a new direction. My students were using platforms like MySpace to say things about themselves, to give their opinions, and to challenge each others’ ideas. It was entirely social, but what they were doing was writing, sometimes with letters and words, sometimes with images. But it’s all text, and that’s what drew me in. So I tried again.

This all happened at the turn of the century, but the idea of 21st century literacy wasn’t on my radar. I wasn’t thinking about how drastically teaching reading and writing was going to be impacted by the World Wide Web. I just wanted to be in on what was happening. Though my first failures did send me in a new direction. My students were using platforms like MySpace to say things about themselves, to give their opinions, and to challenge each others’ ideas. It was entirely social, but what they were doing was writing, sometimes with letters and words, sometimes with images. But it’s all text, and that’s what drew me in. So I tried again. the way my students wrote. Their voices faded. Those few times I did manage to spark something good–thoughtful, honest writing with authentic voices about a text we were looking at–then their writing became self supporting. Students abandoned me as audience and wrote for each other, fed off each other and it had very little–actually nothing–to do with me. In fact, I was very careful not to enter into the conversation because as soon as I said anything, their writing changed course and was directed at replicating the thing I’d praised. The writing even changed when students knew that I was lurking but not writing anything. Many of them would lose the nerve to be the writers they really were. It didn’t matter that I told them that their audience was each other; my mere virtual presence changed how they wrote. When I became their audience, they tried to write like students. But when their audience was other students, they wrote like writers. They had more confidence, took risks, and tried to engage the each other. In short, they did what writers do.

the way my students wrote. Their voices faded. Those few times I did manage to spark something good–thoughtful, honest writing with authentic voices about a text we were looking at–then their writing became self supporting. Students abandoned me as audience and wrote for each other, fed off each other and it had very little–actually nothing–to do with me. In fact, I was very careful not to enter into the conversation because as soon as I said anything, their writing changed course and was directed at replicating the thing I’d praised. The writing even changed when students knew that I was lurking but not writing anything. Many of them would lose the nerve to be the writers they really were. It didn’t matter that I told them that their audience was each other; my mere virtual presence changed how they wrote. When I became their audience, they tried to write like students. But when their audience was other students, they wrote like writers. They had more confidence, took risks, and tried to engage the each other. In short, they did what writers do.